A status offense is a nondelinquent (and noncriminal) act that is illegal for underage individuals (usually age 17 or younger), but not for adults. There are five main types of status offenses: 1) truancy, 2) running away from home, 3) violating curfew, 4) violating underage liquor laws, and 5) ungovernability. Tobacco offenses and a variety of other acts may also be regarded as status offenses (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2022).

Some engagement in status offending may be considered a normal part of growing up (Jafarian and Ananthakrishnan, 2017; Jennings, Gibson, and Lanza-Kaduce, 2009). However, researchers have found that status offense behaviors sometimes signal the presence of underlying issues (Jafarian and Ananthakrishnan, 2017) and can be associated with adverse youth outcomes such as substance misuse (Henry and Huizinga, 2007; Sultan et al., 2023; Tucker et al., 2011), victimization (Kim et al., 2009), delinquency, criminality, and being arrested as an adult (Benoit-Bryan, 2011; Jennings, 2011; Kim et al., 2009).

State statutes vary in their definitions of status offending and in their approaches to addressing status offense cases. When referred to court, these cases are also called person/child in need of supervision (PINS/CHINS), child requiring assistance (CRA), child in need of aid (CINA), child in need of care, or unruly child (JJGPS, 2015; Smoot, 2015). States that voluntarily receive funding from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), as part of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act's (JJDPA's) Title II Formula Grants Program, must commit to achieving and maintaining compliance with deinstitutionalizing youth who engage in status-offending behaviors.

This literature review defines key terms, discusses risk factors for status offending, summarizes how states and the federal government address status offending, and presents data and information on juvenile court processing and the characteristics of youth in the juvenile justice system for status offenses. The characteristics and outcomes of programs addressing status offending are described.

This section provides definitions related to status offenses, including terms used to describe juvenile court processing and the types of status offenses. The collection of data on status offending is also discussed.

Status offenses are acts that are illegal only because the individual committing them is a minor; these acts are not illegal when committed by an adult. Status offense cases are processed in juvenile court, which is any court that has jurisdiction over matters involving juveniles as defined by state law. For more information, see the OJJDP literature review Age Boundaries of the Juvenile Justice System.

The five main types of status offenses are defined below.

- Truancy refers to violating compulsory school attendance laws (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). Some studies of truancy also examine absenteeism. Whereas truancy generally applies only to unexcused absences, absenteeism incorporates all types of absences, which can include excused absences, unexcused absences, and suspensions (Burr, Ziegler-Thayer, and Scala, 2023; Milligan, 2024; Treglia, Cassidy, and Bainbridge, 2023; Van Eck et al., 2017). Truancy is a status offense, but chronic absenteeism is not.

- Runaway offenses refer to leaving the custody and home of parents, custodians, or guardians without permission and failing to return within a reasonable length of time, in violation of a statute regulating the conduct of youth (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024).

- Curfew violations occur when youth are found in a public place during specified hours, usually established in a local ordinance applying only to persons under a specified age (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024; Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2023a). Youth curfew ordinances are sometimes called youth curfew laws or curfew statutes (Wilson et al., 2016; Stoddard et al., 2015; Korecky, 2016). Youth curfew laws are generally related to nighttime (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024), but they may be in place to restrict specific activities for youth, such as driving after a certain hour of the day (Wilson et al., 2016; Adams, 2003). Violating certain types of curfew laws and restrictions is not considered a status offense. Two examples are emergency curfews, which are implemented during brief periods for individuals of all ages, in the interest of public safety, often during state-of-emergency declarations or in response to mass protests (Apel, Rohde, and Marcus, 2023; Loor, 2019; Norton, 2013; Ugwu, 2022); and curfews used as a condition of probation in delinquency cases or as part of a diversion agreement. Breaking an emergency curfew is treated as a misdemeanor or delinquent offense, and breaking a curfew that is a condition of probation or part of a diversion agreement is regarded as a technical violation.

- Underage use of alcohol, also known as status liquor law violations, includes the violation of laws regulating the possession, purchase, or consumption of liquor by minors. Nationally, courts are more likely to consider alcohol violation cases involving youth to be status offenses, though they may also be considered delinquency offenses (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). In 2022, about 10 percent of liquor law violation cases petitioned in juvenile court were treated as delinquency offenses while 90 percent were treated as status offenses (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:36, 64).

- Ungovernabilityrefers to being beyond the control of parents, guardians, or custodians or being disobedient of parental authority. This classification is referred to in various juvenile codes as unruly, unmanageable, incorrigible, or beyond the control of one's parents (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2019; CJJ, 2013; Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). This status offense type is different from permanent incorrigibility (also called irreparable corruption and incapable of reform), which is a concept used to determine whether to sentence a youth to life without parole in serious cases (LDF, 2021; Matsumoto, 2020) and is not a status offense.

Unlike status offenses, delinquency offenses are acts committed by a youth that would be criminal if committed by an adult and could result in criminal prosecution. Delinquency offenses include offenses against persons, such as simple assault, aggravated assault, sexual assault, robbery, and homicide; property offenses, such as burglary, theft, and arson; drug offenses, including the unlawful sale, purchase, distribution, manufacture, cultivation, transport, possession, or use of a controlled or prohibited substance or drug; crimes against public order, such as disorderly conduct, obstruction of justice, and weapons offenses (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024; Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2023a); and other offenses that would result in criminal prosecution if committed by an adult.

When youth are referred to juvenile court, there is generally an intake department that screens the cases. In most cases, the intake department may decide to 1) dismiss a case for lack of legal sufficiency; 2) resolve the case informally, which is often called a nonpetitioned case; or 3) resolve the matter formally, which is often called a petitioned case. Petitioned status offense and delinquency cases appear on the official court calendar and are scheduled for adjudicatory hearings. Adjudication is the juvenile court process through which a judge determines whether a youth is responsible for the offense. The term adjudicated in juvenile court can be considered analogous to the term convicted in adult court and indicates that the court concluded the juvenile is responsible for the act or offense. After adjudication, at the disposition hearing, the judge determines the most appropriate sanction (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:96-97). The most common disposition for youth adjudicated for status offenses is probation. Other dispositions include community-based treatment or counseling, paying restitution or a fine, community service, or placement in a residential program (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:84).

Congress enacted the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) in 1974 (P. L. 93415, 42 U.S.C. § 5601 et seq.). This legislation established the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) to support local and state efforts to prevent delinquency and improve juvenile justice systems. The JJDPA's Title II Formula Grants are awarded to states to support their delinquency prevention and juvenile justice systems improvement efforts. To receive JJDPA Title II Formula Grants funding, states voluntarily commit to achieving and maintaining compliance with the four core requirements: 1) deinstitutionalization of status offenders, 2) separation of youth from adults in secure facilities, 3) removal of youth from adult jails and lockups, and 3) addressing racial and ethnic disparities within juvenile justice systems. In December 2018, the Juvenile Justice Reform Act (JJRA) of 2018 was signed into law, reauthorizing and amending the JJDPA.

Risk factors are characteristics that influence the likelihood of adverse outcomes such as status offending, delinquency, and juvenile justice system involvement. Researchers have identified risk factors associated with engaging in status-offending behaviors at the individual, family, peer, school, and community levels. Most of this research examines specific offenses, primarily truancy, running away, and underage drinking. Each of these three status offenses is associated with risk factors such as low levels of school engagement and poor school performance (e.g., CDC, 2024; Tucker et al., 2011; Vaughn et al., 2013), family dysfunction (e.g., CDC, 2023b; Hunt and Hopko, 2009; Radu, 2017), and association with delinquent or status-offending peers (e.g., Baek and Lee, 2020; Castillo et al., 2023; Maynard et al., 2017). Other factors have also been identified, as described below.

Truancy

Individual-level risk factors associated with truancy include propensity to take risks (Maynard et al., 2017); fighting and other externalizing behaviors (Maynard et al., 2017; Vaughn et al., 2013); having depression (Finning et al., 2019; Hunt and Hopko, 2009); and substance misuse (Henry, 2007; Maynard et al., 2017). Some studies have found that demographic characteristics such as sex, race, and ethnicity influence truancy, while other studies do not find a significant influence. For example, some studies find that girls are more likely to be truant than boys (e.g., Maynard et al., 2017), others find that boys are more likely to be truant than girls (e.g., van der Aa et al., 2009), and some studies have found no relationship by sex (e.g., Barthelemy et al., 2022).

Family-level factors related to truancy include low socioeconomic status (Nolan et al., 2013; Sosu et al., 2021), low levels of parental involvement and supervision after school (Henry, 2007; Vaughn et al., 2013), parents with fewer years of formal education (Henry, 2007; Hunt and Hopko, 2009), and unstructured home environments (Hunt and Hopko, 2009). For example, a large study examining the relationship between parental involvement and skipping school found that youth who reported skipping school were 40 to 75 percent less likely to have an involved parent (Vaughn et al., 2013). The study authors used 2009 data on more than 17,000 youth participating in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Parental involvement was measured by asking questions about how often parents provided positive reinforcements, limited time for going out on school nights, and helped with homework.

School-level factors include frequent school changes (Nolan et al., 2013), special education status (Nolan et al., 2013), involvement with delinquent and substance-using peers (Henry and Huizinga, 2007; Maynard et al., 2017), and poor school engagement and performance (Henry, 2007; Henry and Huizinga, 2007; Hunt and Hopko, 2009; Maynard et al., 2017; Vaughn et al., 2013). A large study found that lower academic engagement and school grades were correlated with truancy for each of the three examined races/ethnicities: non-Hispanic white, Black, and Hispanic (Maynard et al., 2017). The study analyzed data collected between 2002 and 2014 for more than 200,000 youth in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Non-Hispanic white students with usual grades of D or lower were 1.9 times more likely to be truant than white youth with A averages; Black students with usual grades of D or lower were 1.7 times more likely to be truant than Black students with A averages; and Hispanic students with usual grades of D or lower were 2.1 times more likely to be truant than Hispanic students with A averages. Also, students who were more academically engaged were 6–7 percent less likely to be truant than students who were less engaged. Academic engagement was assessed with a five-item scale measuring perceived importance and interest in learning and school activities (e.g., "During the past 12 months, how often did you feel that the schoolwork you were assigned to do was meaningful and important?") [Maynard et al., 2017].

Running Away

Researchers have examined the risk factors related to running away from home (e.g., Castillo et al., 2023; Radu, 2017), running away from foster care (e.g., Byers et al., 2024; Courtney and Zinn, 2009; Crosland et al., 2018), and running away from other residential placements (e.g., Bartoszko and Herland, 2024).

Risk factors with the strongest influence on running away include individual factors such as being female (Branscum and Richards, 2022; Castillo et al., 2023; Radu, 2017; Tyler, Hagewen, and Melander, 2011; Wulczyn, 2020); identifying as LGBQ (Benoit-Bryan, 2011; Radu, 2017; Waller and Sanchez, 2011); defiant, aggressive, delinquent, and sensation-seeking behaviors (Castillo et al., 2023; Holliday, Edelen, and Tucker, 2017); substance misuse (Branscum and Richards, 2022; Castillo et al., 2023; Holliday, Edelen, and Tucker, 2017; Tucker et al., 2011); and mental health problems (Courtney and Zinn, 2009; Radu, 2017; Tucker et al., 2011). For example, researchers examined data on more than 100,000 youth who participated in the Monitoring the Future study, which is an ongoing study of the attitudes, behaviors, and values of Americans from adolescence through adulthood; they found that low self-esteem, alcohol use, marijuana use, cigarette use, sensation seeking, interpersonal aggression, and self-derogation were associated with higher odds of running away from home by tenth grade (Castillo et al., 2023).

Also, a longitudinal study of more than 5,000 students from 62 middle schools in North Dakota examined several predictors of running away by tenth or eleventh grade (Tucker et al., 2011). The researchers found that depressive affect (measured by calculating the amount of time in the past month the respondent felt "depressed, blue, and down in the dumps") was associated with running away overnight or longer in the past year.

Family risk factors include family instability and lack of parental support (Castillo et al., 2023; Tucker et al., 2011; Tyler, Hagewen, and Melander, 2011), not living with two parents (Radu, 2017), living in foster care or other out-of-home care settings (Benoit-Bryan, 2011; Radu, 2017), and physical or psychological abuse (Benoit-Bryan, 2011; Kim et al., 2009). Analysis of data from more than 15,000 youth participating in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health determined that more than 30 percent of respondents who had been in foster care as an adolescent had also run away from home, compared with 8 percent of individuals who had no foster care history (Benoit-Bryan, 2011). The study also found that individuals who were verbally abused before age 18 were more than twice as likely to run away from home compared with those who were not verbally abused. Additionally, the likelihood of running away from home was three times higher for respondents who were physically abused compared with those who were not; and children who were sexually abused were more than twice as likely to have run away from home as those who were not sexually abused.

Other risk factors for running away include school disengagement (Tucker et al., 2011), low GPA (Castillo et al., 2023), and deviant peers (Castillo et al., 2023; Chen, Thrane, and Adams, 2012; Radu, 2017). Analysis of data from more than 7,000 youth participating in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found that friends' minor deviance was related to how often respondents ran away from home in the last 12 months (Chen, Thrane, and Adams, 2012). Minor deviance was measured by how often the respondent's friends committed six minor deviant activities: 1) doing something dangerous on a dare, 2) smoking cigarettes, 3) drinking alcohol, 4) getting drunk, 5) racing vehicles such as cars or motorcycles, and 5) skipping school without an excuse.

Risk factors for running away specific to youth in foster care include having a history of placement in congregant care (Wulczyn, 2020) and being placed in foster care for reasons such as child substance abuse, abandonment, and child behavioral problems (Branscum and Richards, 2022). Research examining running away from other types of residential placements is mostly conducted internationally (e.g., Bartoszko and Herland, 2024; Kerr and Finlay, 2006; Sunseri, 2003) and is not included in this literature review.

Underage Drinking

Risk factors for underage drinking have been identified in all domains. Individual-level factors include low levels of self-control, risk-taking propensity, impulsivity, and sensation-seeking behaviors (Baek and Lee, 2020; Baek, Lee, and Posadas, 2022; MacPherson et al., 2010; Norman et al., 2011); a history of sexual violence victimization (CDC, 2023a); and a history of delinquent behavior (Donovan, 2004). Researchers analyzed data from more than 15,000 high school students participating in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey who answered questions about both alcohol use and sexual violence victimization. They found that 43 percent of the students who had reported experiencing sexual violence also reported being current alcohol drinkers, compared with only 19 percent of the students without histories of violence (CDC, 2023a).

Family-level factors include not living with both parents (Baek and Lee, 2020; Donovan and Molina, 2011), lack of parental supervision and poor parenting (Baek, Lee, and Posadas, 2022; CDC, 2023b), child abuse and neglect (Shin, Edwards, and Heeren, 2009), and having a parent with mental illness (CDC, 2023c). A longitudinal study of 452 children in Allegheny County, PA, examined the influence of about 50 variables (related to personality, behavior, peers, and family) on early alcohol initiation, defined as drinking before age 14 (Donovan and Molina, 2011). The researchers found that the strongest predictors of early alcohol initiation were having parents who drink frequently or who started drinking before age 14, living in a single-parent household, and sipping alcohol before age 10.

Peer-level factors related to underage drinking include affiliation with alcohol-using or deviant peers (Baek and Lee, 2020; Donovan, 2004; Leung, Toumbourou, and Hemphill, 2014) and exposure to social media posts showing friends with alcohol (Vanherle, Beyens, and Beullens, 2024). School-level factors include lower grades (CDC, 2024). Community-level risk factors include alcohol accessibility (Baek and Lee, 2020) and exposure to alcohol marketing (Sargent and Babor, 2020). Analysis of data from the Monitoring the Future: A Continuing Study of American Youth survey examined the effect of "opportunity" on underage drinking (Baek and Lee, 2020). The authors of the study defined opportunity as the accessibility of drinking alcohol at the community level (e.g., "How difficult do you think it would be for you to get alcohol if you wanted some?") and peer level (e.g., "How many of your friends would you estimate get drunk at least once a week?"). They found that opportunity was the most significant factor related to underage drinking, and that it was more significant than low self-control, sex, family structure, or religion.

The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) was passed in 1974, encouraging a federal-state partnership for the administration of juvenile justice. The Act has been updated and reauthorized several times, the latest being in 2018. In its infancy, the Act set two core requirements for states to receive federal funding: 1) the separation of youth and adults when held in jails, lockups, or other secure settings ("sight and sound separation"), and 2) the deinstitutionalization of status offenders (DSO). Later, two more requirements were added: 3) removal of youth from adult jails and lockups ("jail removal"), limiting the detainment of youth in adult jails and lockups to less than 6 hours (with exceptions); and 4) a requirement that states assess and address racial and ethnic disparities within their juvenile justice systems (Ames, 2024; OJJDP, n.d.).

The DSO core requirement of the JJDPA established that youth charged with status offenses, and abused and neglected youth, shall not be placed in secure detention or locked confinement (34 U.S.C. § 11133(a)(11)(A)). One of the purposes of this requirement was to encourage states to divert status-offending youth away from the juvenile justice system and place them in less restrictive, more service-intensive, community-based programs. The DSO requirement reinforces the idea that status offenses are different from delinquency offenses and therefore should be dealt with differently (Ames, 2024).

In 2023, of the 56 states and territories (including the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories), 52 were eligible for funding under the JJDPA Formula Grants program. Of the eligible states and territories, 51 were compliant with the DSO requirement (OJJDP, 2024).

Valid Court Order (VCO) Exception

Although the DSO requirement's intent is to treat youth with status offenses differently from youth with delinquency offenses, youth may be placed in secure detention if they violate a court order. In 1980, the JJDPA was amended to include the valid court order (VCO) exception to the DSO requirement, which permits discretion to place youth with status offenses in detention upon violation of a previously established court order (U.S.C. 11133(a)(23)).

Some studies have found that youth who are on probation because of status offenses violate their conditions of probation more quickly compared with youth on probation for misdemeanor and felony offenses (e.g., Dir et al., 2021). These technical violations are noncriminal, nondelinquent incidents such as failure to meet with a probation officer, failure to provide a urine drug test, or school absence during a period of required attendance. Penalties for technical violations may include secure detention, additional probation requirements, or an extended probation period, which may increase the odds of another violation (Ingel et al., 2022; Jafarian and Ananthakrishnan, 2017; Robin, Henderson, and Jackson, 2023).

The Juvenile Justice Reform Act (JJRA) of 2018 was signed into law, reauthorizing and amending the JJDPA and imposing additional requirements for using the VCO exception. One of the changes was the requirement that, within 48 hours after the juvenile is taken into custody for violating the VCO, if the court determines that placement in a secure detention or secure correctional facility is warranted, the court must issue a written order setting out the specific factual circumstances surrounding the violation of the VCO. Such placement may not exceed 7 days and the court's order may not be renewed or extended. A second or subsequent order is not permitted with respect to the violation of a particular VCO. The JJRA also added a requirement that procedures be in place to ensure that a youth with a status offense is not detained for more than 7 days or longer than the length of time directed by the court (whichever is shorter) [Section 223(a)(23) of the JJDPA; OJJDP, 2019].

In 2021, OJJDP found that 13 states that claim the VCO exception used it in 1,411 cases. The states with the largest number of VCO exceptions were Ohio (981 exceptions), Mississippi (117 exceptions), and Wisconsin (106 exceptions). The total number of cases with VCO exceptions has decreased over time. In 2016, there were 5,085 VCO cases in 24 states that claim it; in 2014, there were 7,466 VCO cases in 27 states; and in 2013, there were 8,227 VCO cases in 27 states (OJJDP, 2015; OJJDP, 2022).

Status offense laws and terminology differ by state. Regardless of the state, most status-offending behaviors never come to the attention of the court for formal processing. For example, alcohol is the most common drug used by people younger than 21 in the United States (CDC, 2025). In 2021, about 23 percent of high school students reported using alcohol in the past 30 days (defined as "current use"), and 47 percent reported using alcohol at least once (CDC, 2023d). However, only about 5,000 status offense cases for liquor law violations were petitioned in juvenile court in 2022. Similarly, some sources report that more than a million youth run away each year (e.g., OJJDP, 2019a; OJJDP, 2019b), but fewer than 6,000 status offense cases were petitioned in juvenile court for running away in 2022.

In 2022, juvenile courts petitioned and formally disposed about 62,000 status offense cases nationally. Laws, diversion policies, and sanctions following case disposition vary among states (Smoot, 2015). Also, states use a variety of terms to describe status offense cases including person/child in need of supervision (PINS/CHINS), child requiring assistance (CRA), child in need of aid (CINA), child in need of care, unruly child, or families in need of assistance (FINS) [JJGPS, 2015; Kendall and Hawke, 2007; Smoot, 2015]. Some states have specialized courts specifically for truancy (e.g., Gray, 2023; Hendricks et al., 2010).

The different frameworks that states use to treat status offenses range from the child welfare perspective, which is more likely to treat the youth as victims, to the public safety perspective, which is more likely to treat the youth as offenders (JJGPS, 2015; Ricks and Esthappan, 2018). States' responses to status offending can also be classified as 1) deterrence, 2) treatment, or 3) normalization (Jennings, Gibson, and Lanza-Kaduce, 2009). The deterrence approach is based largely on the view that status offenses harm the community and that youth who engage in these behaviors will escalate to more serious delinquency if not punished (Jennings, Gibson, and Lanza-Kaduce, 2009; Lipsey, 2009; Singer and McDowall, 1988). In the treatment approach, child welfare, mental health, and other treatment agencies are called upon to address the youths' underlying needs, which may include mental health issues and family problems, to prevent more serious behaviors (Jennings, Gibson, and Lanza-Kaduce, 2009). Normalization is based on the theory that it is best to take a hands-off approach because the behavior is either harmless or will resolve on its own and because court involvement may have a stigmatizing effect, leading to a negative self-concept for the youth and adverse future outcomes (Barrick, 2017; Bernburg, Kroh, and Rivera, 2006; Cullen and Johnson, 2014; Jennings, 2011; Kroska, Lee, and Carr, 2017; Restivo and Lanier, 2015). Agencies that incorporate a normalization approach may focus on diverting these cases away from court or not involving them in formal court processing at all.

In 2023, about half of U.S. states processed children and youth with status offenses in the same court as children and youth with delinquency charges (CSG, 2024). About two thirds of states allow youth who commit status offenses to be held in police custody, and about 40 percent allow youth with status offenses to be incarcerated (CSG, 2024). In more than 80 percent of states, parents can be sanctioned in court if their child commits a status offense or disobeys a court order (CSG, 2024). In about 70 percent of states, youth with status offenses may be placed on probation (CSG, 2024). Also, most states authorize referrals to nonsecure residential placements.

Additionally, many individuals with status offenses are diverted from formal juvenile justice processing (Schwalbe et al., 2012; Wilson and Hoge, 2013). In most states, court officials have the authority to informally adjust a status offense case or to divert the youth to a service program instead of hearing the matter in court, and several states make diversion a requirement (Smoot, 2015). Diversion redirects youth away from formal justice system processing and can occur in lieu of arrest or after juveniles are referred to court (DSG, 2017; Smoot, 2015). Diversion programs range from low intensity warn-and-release policies to comprehensive interventions involving individualized services and multiple partners (Smoot, 2015; Schwalbe et al., 2012; Wilson and Hoge, 2013).

Many jurisdictions give responsibility to agencies other than juvenile courts (such as family crisis units, county attorneys, and social service agencies) for processing status offenses (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). In these jurisdictions, youth with status offenses would not have contact with the juvenile court.

When a youth charged with a status offense is referred to court, the options generally include either diversion away from the formal justice system or formal processing by the filing of a court petition. Petitioned status offense cases may be adjudicated and may receive a disposition by the juvenile court. While a status offense case is being processed through the juvenile court system, youth may be held in secure detention at some point between referral and final disposition. In a small percentage of cases, youth may be sent to a residential placement as a disposition (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024).

Petitioned Cases

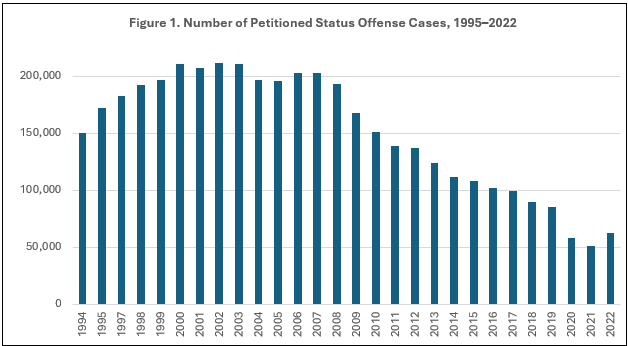

In 2022, courts with juvenile jurisdiction petitioned and formally disposed about 62,000 status offense cases. Since 2007, the number of status offense cases decreased each year until 2021 (see Figure 1). In 2000, there were four times as many status offense petitions as there were in 2021. However, 2022 saw an increase in status offense cases, which appears to have been driven by an increase in truancy cases (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:64).

In 2022, the most common petitioned status offense cases were truancy (64 percent of all status offense cases), followed by running away (9 percent) underage drinking violations (8 percent), ungovernability (8 percent), curfew violations (3 percent), and miscellaneous (8 percent) [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:65]. Most of these cases (62 percent) were referred to court by schools and 14 percent were referred by police departments. Referral sources differ greatly by offense. Curfew violation cases were the most likely to have been referred by police (87 percent), and truancy cases were the least likely to be referred by police (2 percent). Relatives were the referral source for 44 percent of the petitioned ungovernability cases and about 30 percent of the runaway cases (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:76).

Detention

Detention refers to placement in a secure facility under court authority at some point between the time of referral to court intake and case disposition (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:95). In 2022, there were 2,000 status offense cases involving secure detention. This number represents 3 percent of the petitioned status offense cases. Over the past 15 years (from 2005 to 2022), the number of petitioned status offenses involving detention decreased by 90 percent (from 20,300 to 2,000), an even greater decrease than the number of petitioned status offenses (which decreased 74 percent). The decrease was gradual and generally consistent over the 15 years (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:76).

For at least the past 15 years, truancy has been the least likely of all the status offenses to involve secure detention. However, truancy accounted for one quarter of all status offense cases involving detention because truancy cases far outnumbered other types of status offense cases. The status offense types with the highest probability of detention have changed over time, but since 2019, youth in runaway and ungovernability cases were the most likely to receive detention (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:76).

Adjudication

Adjudication is the judicial determination (judgment) that a juvenile is responsible for the delinquency or status offense charged in a petition (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:95). The likelihood of adjudication in petitioned status offense cases was 28 percent in 2022. Adjudication was least likely in petitioned truancy cases (21 percent) and runaway cases (21 percent) and most likely in cases involving curfew violations (51 percent) and liquor law violations (51 percent) [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:85].

Disposition

A disposition is a treatment plan or sanction ordered in an adjudicated case (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:95–96). In 2022, formal probation, also called court-ordered supervision, was the most restrictive sanction ordered by the court in more than half of adjudicated status offense cases (65 percent). Only 10 percent of adjudicated cases resulted in out-of-home placement, and 25 percent involved another sanction such as restitution or a fine, an order to enter treatment or counseling, or community service. Out-of-home placement and probation were less likely in status offense cases than in delinquency cases (28 percent of adjudicated delinquency cases resulted in out-of-home placement, and 67 percent resulted in probation) [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:80].

Among the five most common types of petitioned status offense cases, youth in ungovernability cases were the most likely to receive out-of-home placement (92 placements per 1,000 petitions), followed by runaway cases (39 placements per 1,000 petitions). Runaway cases were also the most likely to be dismissed after petition (718 dismissals per 1,000 petitions). Liquor law violations were the most likely to result in probation (309 probation placements per 1,000 petitions), and curfew violation cases were the least likely to result in probation (89 probation placements per 1,000 petitions) [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:85].

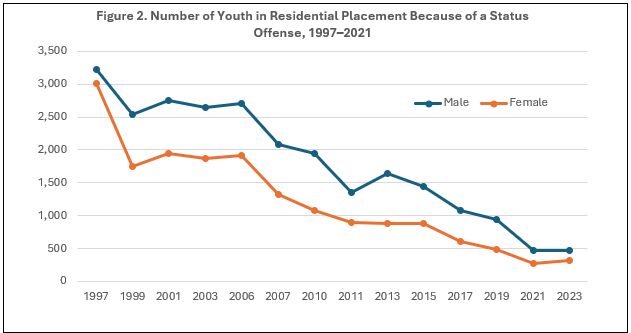

The Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (CJRP) is a biennial census of youth in secure and nonsecure juvenile residential placement administered by OJJDP that collects a one-day count of youth in placement on a given day. In 2023, the CJRP found that 777 youth were in residential placement because of a status offense, which represented less than 3 percent of the total youth residential population. These youth included 464 boys and 313 girls (Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2025b). The number of youth in residential placement because of status offenses has declined considerably since the late 1990s (see Figure 2). From 1997 to 2021, the number decreased by 88 percent. In other words, 8.5 times more youth were in residential placement because of a status offense in 1997 than in 2021. In 2023, the number increased slightly.

In 2021, about 34 percent of youth with status offenses in residential placement had been adjudicated for ungovernability/incorrigibility, 20 percent for running away, 16 percent for truancy, 4 percent for underage drinking, 4 percent for curfew violations, and 22 percent for other status violations (Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2023d). Residentially placed youth with status offenses were in the following types of facilities: 45 percent, residential treatment centers; 22 percent, group homes; 16 percent, shelters; 16 percent, detention centers; 1 percent, long-term secure facilities; and fewer than 1 percent, wilderness camps, boot camps, or diagnostic centers (Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2023c). More than 90 percent of the youth were in facilities where residents were restricted within the facility or its grounds by locked doors, gates, or fences some or all the time (Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2023c).

This section presents information on the basic characteristics of status offense cases petitioned in juvenile courts in the United States in 2022. Also discussed are the demographics of youth in residential placements in 2021.

Age

In 2022, the petitioned case rate for status offenses increased with age, until age 16. There were 3.3 petitioned status offense cases per 1,000 16-year-olds, compared with a rate of 3.1 for 15-year-olds, 2.3 for 14-year-olds, 1.6 for 13-year-olds, and fewer than 1.0 for 10-, 11-, and 12-year-olds. The status offense case rate was 2.3 for 17-year-olds. For each age group, the petitioned case rate increased from 2021 to 2022 (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:66–67).

Among youth in residential placement for status offenses in 2023, about 9 percent were age 13 or younger, 16 percent were 14 years old, 22 percent were 15 years old, 24 percent were 16 years old, 21 percent were 17 years old, and 8 percent were ages 18–20 (Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2025b).

Sex

In 2022, boys were overrepresented among youth with petitioned status offenses in juvenile court, accounting for 54 percent of the petitioned status offense caseload. In 2022, boys accounted for most of the petitioned curfew violation cases (65 percent), liquor law violation cases (58 percent), truancy cases (54 percent), and ungovernability cases (53 percent) cases. Girls accounted for most of the petitioned runaway cases (58 percent) [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:69].

Among youth in residential placement for status offenses in 2023, 60 percent were boys and 40 percent were girls (Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2025a). Girls comprised a larger percentage of runaway cases (51 percent). Boys comprised a larger percentage of curfew violations (82 percent), truancy (69 percent), incorrigibility (61 percent), underage drinking (51 percent), and other status offense cases (70 percent) [Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2025c].

Race/Ethnicity

In 2022, 58 percent of the petitioned status offense cases involved white youth, 25 percent involved Black youth, 11 percent involved Hispanic youth, 4 percent involved American Indian youth, and 2 percent involved Asian youth (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). Also in 2022, the status offense petition rates (cases per 1,000 youth) were highest for American Indian youth, followed by Black youth. Hispanic and Asian youth had the lowest status offense petition rates.

Among youth with residential placements for status offenses in 2023, 47 percent were white, 34 percent were Black, 13 percent were Hispanic, 2 percent were American Indian, 4 percent were more than one race, and less than 1 percent were Asian or Pacific Islander (Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2025b). The residential placement rate (per 100,000 youth) was highest for Black youth (6 per 100,000), followed by American Indian youth (5 per 100,000), white youth (2 per 100,000), youth with more than one race (2 per 100,000), and Hispanic youth (1 per 100,000) [Puzzanchera, Sladky, and Kang, 2025c].

A variety of programs have been developed for children and youth who are at risk of, or who engage in, status-offending behaviors. Some programs are designed to prevent and intervene in status-offending behaviors directly, while others target problem behaviors in general but can also be used to treat status-offending youth. Typically, programs in the latter category treat youth with multifaceted needs and indirectly target the needs of status-offending youth. Still, other programs provide services to youth who are already engaged in status offending, to prevent additional adverse outcomes.

Programs Addressing Truancy

Meta-analytic research examining studies of targeted truancy programs has found that they can improve school attendance (Klima, Miller, and Nunlist, 2009; Maynard et al., 2012). All truancy programs have a short-term goal of improving attendance, and many programs also have longer-term goals of raising grades and graduation rates. Types of initiatives include prevention programs, which may target all students in an elementary, middle, or high school; intervention programs, which may engage youth who have already started to skip school; and comprehensive programs for chronically truant youth.

For example, the Check & Connect Plus Truancy Board (C&C+TB) is a school-based program that integrates a case management framework for providing social support to truant youth. The truancy board, which consists of 5–10 members (including school administrators, volunteers from social service agencies and local businesses, and a juvenile court probation counselor) seeks to collaboratively engage youth and their families in accessing a variety of resources to improve school attendance, promote school attachment, and enhance academic achievement. Program participants and their families meet with the truancy board individually to 1) discuss truancy laws and legal consequences of continued truant behavior, 2) identify obstacles to attendance, and 3) collaboratively develop a formal agreement outlining the specific steps the student and family will take to improve attendance. An evaluation of C&C+TB with a sample of 132 students in Spokane, Washington, found that students who participated in the programs were statistically significantly more likely to have graduated and less likely to have dropped out of school than students in a comparison group (Strand and Lovrich, 2014).

The Ability School Engagement Program is a police-school partnership intervention that seeks to reduce antisocial and truant behaviors among youth and increase their willingness to attend school. The intended population is students ages 10–16 with a record of attending 85 percent of school days or less without a legitimate explanation (such as medical illness) for their absences. Evaluations of the implementation of this program in Australia found that it reduced truancy: participating students were statistically significantly less likely to miss school and more likely to report being willing to attend school, compared with students who did not participate in the program (Bennett et al., 2018; Mazerolle et al., 2017).

The Resilience, Opportunity, Safety, Education, Strength (ROSES) program is a community-based, trauma-informed intervention for adolescent girls ages 11–17 who are at risk of being, or already are, involved in the juvenile justice system. The program's goals are to promote the girls' positive development by strengthening their protective contexts (e.g., school, family, peers) and decrease the girls' engagement with risk-enhancing contexts (e.g., antisocial peers, the juvenile justice system). The intervention lasts 10–12 weeks and involves a university-community partnership. Advocates, who are advanced undergraduate students from a local university, meet in the community with their assigned girls twice a week and engage in advocacy work for about 10 hours each week. An evaluation of ROSES was conducted in New York City with girls who had excessive school absenteeism, truancy, or previous police contact. The evaluation found that participating in ROSES resulted in a statistically significant lower number of school absences, compared with not participating. Girls who participated in ROSES also demonstrated fewer physical fights than girls who did not participate (Javdani and Daneau, 2020).

The School District of Philadelphia's nudge messaging approach uses a "nudge" postcard to reduce student absenteeism by increasing parents' or guardians' awareness of nonattendance. Parents or guardians of students in grades 1–12 received postcards with one of the two following messages: 1) a general version that encourages guardians to improve their student’s attendance, and 2) a more specific version that encourages guardians to improve their student’s attendance by including specific information about the child's attendance history. The postcards were mailed from the superintendent's office with the student report cards. An evaluation of this intervention found a statistically significant decrease in posttreatment absenteeism among the children of parents or guardians who received the messages, compared with the children of parents or guardians who did not receive the messages (Rogers et al., 2017).

Programs Addressing Running Away

The two programs described below are designed for youth who have run away from home. There are also runaway prevention programs (e.g., Pergamit, 2016), but most do not yet have rigorous evaluations examining their effectiveness.

Ecologically Based Family Therapy (EBFT) is a home-based, family preservation model that focuses on families in crisis because a youth has run away from home. EBFT targets adolescents ages 12–17 who are staying in a runaway shelter and are also dealing with substance use issues (such as alcohol dependence). The goal of EBFT is to improve family functioning and reduce the teens' substance use. The program is delivered to families in their homes through 16 sessions, lasting 50 minutes each. Evaluators who studied EBFT’s impact on a sample of adolescents and their families found that, at the 9- and 15-month follow-up, adolescents in the EBFT group reported a statistically significantly lower percentage of days of alcohol or drug use, compared with adolescents who did not participate in EBFT (Slesnick and Prestopnik, 2009). However, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups on any other measure of substance use at the follow-up periods.

Aggression Replacement Training (ART) for Adolescents in a Runaway Shelter is a program that combines anger control training, social skills training, and moral reasoning education to alter the behavior of adolescents living in a runaway shelter who have exhibited antisocial and aggressive behaviors. The program is delivered over a 21-day period. Youth participate in one skills-training group each day, focused on anger reduction, anger triggers, how to express a complaint, the use of self-instruction, how to resist group pressure, self-evaluation, consequential thinking, how to respond to the anger of others, the angry behavior cycle, how to keep out of fights, how to deal with an accusation, empathy, and a review of all the skills taught. An evaluation of this intervention with more than 500 youth found that participants exhibited a statistically significant decrease in antisocial behavior incidents following program implementation (Nugent, Bruley, and Allen, 1998).

Programs Addressing Underage Drinking

Programs with substance misuse-related goals are often categorized as 1) primary prevention, which seeks to mitigate risk factors and prevent substance misuse from ever developing; 2) secondary prevention, which focuses on identifying a substance misuse condition as early as possible to halt or slow its progression; or 3) tertiary prevention, which strives to minimize the negative consequences of substance misuse (Latimore et al., 2023). Other frameworks categorize programs as: 1) universal prevention, which addresses an entire population to prevent or delay substance misuse; 2) selective prevention, which targets subsets of the population deemed to be at risk for substance misuse; 3) indicated prevention, which is designed to prevent the onset of substance misuse among individuals who show early danger signs; 4) treatment; and 5) recovery (Begun, 2019; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009; STPAC, 2023). The programs highlighted below represent several of these types of interventions.

Positive Family Supports (PFS) is a family-based intervention conducted in a school setting that addresses family dynamics to prevent substance use and problem behaviors in adolescents. Students are provided with six in-class lessons covering topics such as school success, health decisions, building positive peer groups, the cycle of respect, coping with stress and anger, and solving problems peacefully. PFS also helps parents develop family management skills such as making requests, using rewards, monitoring, making rules, providing reasonable consequences for rule violations, problem-solving, and active listening. The program includes components related to universal prevention, selected intervention, and indicated intervention, depending on the needs of participating families. An evaluation of PFS’s implementation (with about 1,000 students ages 11–17 in a metropolitan community in the northwestern region of the United States) determined that the intervention resulted in a statistically significant lower likelihood of alcohol use (Connell et al., 2007). Researchers have also found that this intervention is associated with reductions in cigarette use, marijuana use, and antisocial behavior (Connell et al., 2007; Dishion al., 2002).

Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT) was designed to prevent the development of aggressive and antisocial behaviors in children in elementary school. The program has three main components: 1) classroom-based child social skills training, 2) the playground Good Behavior Game (or GBG), and 3) parent management training. It also focuses on systematic communication between teachers and parents. Evaluations of the program, which was implemented with children living in neighborhoods with higher-than-average rates of juvenile crime, found that elementary school students who participated in LIFT demonstrated statistically significant reductions in the initiation of alcohol and tobacco use as well as decreases in use over time of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs, compared with youth who did not participate in LIFT (DeGarmo et al., 2009; Reid et al., 1999). Participants also demonstrated decreases in physical aggression.

Mystery Shop Programs to Reduce Underage Alcohol Sales is an intervention that seeks to increase staff ID checks for the sale of alcoholic beverages at licensed establishments, to help prevent sales to minors. In the Mystery Shop protocol, a "mystery shopper" between the ages of 21 and 24 enters an alcohol retail outlet and attempts to purchase an alcoholic beverage. If the clerk or server requests and looks at the shopper's ID, the outlet is presented with a green card explaining that the check was correctly performed. If the clerk does not request the mystery shopper's ID or is willing to sell the age-restricted item without examining the ID, the mystery shopper presents the clerk and the manager on duty with a red card. This card indicates a failed ID check and explains the possible penalties that would have occurred if this had been a law enforcement compliance check. A written follow-up report summarizing the Mystery Shop outcome is mailed to the store owner or manager, along with responsible-retailing materials. Although a study that assessed the impact of Mystery Shops in 24 communities in Oregon and Texas did not find any statistically significant effects on ID checks (Krevor, Grube, and DeJong, 2017), another evaluation of Mystery Shop implementation in 16 communities in California, Massachusetts, Texas, and Wisconsin found that the intervention resulted in a statistically significant increase in ID-checking rates from baseline to the end of the intervention period, compared with licensees in the delayed intervention control group (Grube et al., 2018).

The Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS) Community-Based Mentoring Program is intended for children and youth ages 6–18 from single-parent households and low-income neighborhoods. The program involves one-to-one mentoring between a Big Brother or Big Sister (the mentor or adult) and a Little Brother or Little Sister (the mentee or youth) that takes place in a community setting. Matches tend to engage in activities such as going to a movie, attending a sports event, reading books, going on a hike, going to museums, or simply hanging out and sharing thoughts. An 18-month evaluation of the intervention, with more than 1,000 youth in eight sites, found that participation was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the initiation of alcohol and other drug use. Mentored youth also showed statistically significant improvements in their relationships with parents, in school grades, and in school attendance, and a statistically significant reduction in antisocial behavior (Tierney, Grossman, and Resch, 2000).

Programs Addressing Ungovernability/Incorrigibility

Ungovernability (or incorrigibility) refers to behavior beyond the control of parents, guardians, or custodians, or disobedience of parental authority. Most programs do not explicitly describe their participants as "ungovernable" or "incorrigible." However, many programs seek to improve children's and youth's behavior at home and in other settings by helping parents and caregivers improve their parenting strategies.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) teaches parents new interaction and discipline skills to reduce children’s problem behaviors and parental physical child abuse by improving parent-child relationships and parental responses to difficult child behaviors. The intervention is conducted through coaching sessions during which the parent and child are in a playroom while the therapist is in an observation room providing coaching. A study of 54 families with preschool children exhibiting behavioral difficulties in Australia found that participation in PCIT resulted in statistically significantly lower levels of the child’s problem behaviors, compared with nonparticipating families (Nixon et al., 2003). A study conducted with physically abusive families in the United States found that the families who participated in PCIT had statistically significantly fewer reports of child abuse and better parenting behaviors, compared with families who did not participate (Chaffin et al., 2004).

Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) seeks to improve parenting behaviors, which can then lead to improved youth outcomes. ProSAAF is designed to improve family functioning by targeting couple and parenting relationships, promoting positive interactions among couples, and enhancing positive youth development (which includes increasing substance use resistance, reducing conduct problems, and developing a positive self-concept). The program includes six 2-hour sessions, delivered in the home, to maximize fathers' participation. The sessions primarily focus on parents, with youth joining the final 30 minutes of each session. A study of 206 African American families with preadolescent or adolescent children in Georgia found that families who participated in ProSAAF had a statistically significant increase in levels of parental monitoring and in the children's positive self-concept, as well as statistically significant decreases in the children’s conduct problems and substance use initiation, compared with families who did not participate (Beach et al., 2016).

Expanded Early Pathways for Young Traumatized Children is an at-home parent and child therapy program for toddler and preschool children with behavioral and emotional problems who have experienced trauma and live in poverty. The program's goal is to treat and prevent children's disruptive behaviors. This hands-on, instructional treatment approach involves three steps: 1) clinicians describe to parents the rationale for the treatment strategies and model the techniques, 2) parents practice strategies with their child, and 3) clinicians provide direct feedback to parents to ensure appropriate implementation of the strategies. An evaluation of this intervention found that program participation resulted in statistically significant reductions in the child's challenging behaviors and improvement in the quality of caregiver-child relationships (Love and Fox, 2019).

Status offenses are acts that are illegal only because the individuals who commit them are minors; the acts are not illegal when committed by adults. Many of these cases are diverted from the juvenile justice system or are under the purview of other agencies. However, in 2022, courts with juvenile jurisdiction petitioned and formally disposed about 62,000 status offense cases. The most common cases were truancy (64 percent of all status offense cases), followed by running away (9 percent), underage drinking violations (8 percent), ungovernability (8 percent), curfew violations (3 percent), and miscellaneous (8 percent) [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:65]. The number of petitioned status offense cases declined steadily from 2007 to 2021, then increased slightly in 2022 (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024a:64 and 2024b:64).

The deinstitutionalization of status offender (DSO) requirement of the federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act forbids the placement of status-offending youth in secure detention or locked confinement in states that voluntarily participate in the federal program. This requirement reinforces the idea that status offenses should be dealt with differently from delinquency offenses (Ames, 2024). In 2023, 51 of the 57 states (including the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories) were compliant with the DSO requirement (OJJDP, 2024). However, youth may be placed in secure detention if they are on probation and then violate a condition of probation. This placement is allowed under an amendment to the JJDPA called the valid court order (VCO) exception (34 U.S.C. 11133(a)(23)).

A variety of programs have been designed for children and youth who are at risk of status-offending behaviors. Examples include Positive Family Supports (PFS), a family-based intervention conducted in school that reduces the likelihood of alcohol use (Connell et al., 2007); and the Expanded Early Pathways for Young Traumatized Children, a therapy program that prevents disruptive and unruly behavior (Love and Fox, 2019). Other programs work with youth who are already engaging in status-offending behaviors. For example, the Check & Connect Plus Truancy Board (C&C+TB) is a school-based program that helps truant youth improve school attendance and academic achievement (Strand and Lovrich, 2014); and Ecologically Based Family Therapy (EBFT) works with families of teens who have run away and are staying in a runaway shelter (Slesnick and Prestopnik, 2009). In addition to reducing status-offending behaviors, researchers have found that these programs have reduced aggression and antisocial behaviors, school dropout, and use of illegal drugs; and have increased school graduation rates (e.g., Connell et al., 2007; DeGarmo et al., 2009; Strand and Lovrich, 2014).

Adams, K. 2003. The effectiveness of juvenile curfews at crime prevention. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 587(1):136–159.

Ames, B. 2024 (Sept. 6). The history of the 1974 Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act. Article. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

www.ojp.gov/safe-communities/from-the-vault/1974-juvenile-justice-delinquency-prevention-act-history

Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2019 (April 6). What Are Status Offenses and Why Do They Matter? Baltimore, MD. www.aecf.org/blog/what-are-status-offenses-and-why-do-they-matter

Apel, J., Rohde, N., and Marcus, J. 2023. The effect of a nighttime curfew on the spread of COVID-19. Health Policy 129:1–8.

Baek, H., and Lee, S. 2020. Underage drinking in America: An explanation through the lens of the general theory of crime. Deviant Behavior 41(1):17–28.

Baek, H., Lee, S., and Posadas, C.E. 2022. Poor parenting on underage drinking through frustration and impulsivity. Crime & Delinquency 68(10):1898–1917.

Barrick, K. 2017. A review of prior tests of labeling theory. In Labeling Theory: Empirical Tests, edited by D.P. Farrington and J. Murray. Vol. 18 of Advances in Criminological Theory, edited by F. Adler, W.S. Lauter, and F.T. Cullen. New York, NY: Routledge.

Barthelemy, J., Coakley, T.M., Washington, T., Joseph, A., and Eugene, D.R. 2022. Examination of risky truancy behaviors and gender differences among elementary school children. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 32(4):450–465.

Bartoszko, A., and Herland, M.D. 2024. Institutional escapes, breaks, and continuities: Reframing running away from residential child care institutions. The British Journal of Social Work 55(33):1103–1120.

Beach, S.R.H., Barton, A.W., Lei, M.K., Mandara, J., Wells, A.C., Kogan, S.M., and Brody, G.H. 2016. Decreasing substance use risk among African American youth: Parent-based mechanisms of change. Prevention Science 17:572–583.

Begun, A. 2019. Prevention and the continuum of care. In Theories and Biological Basis of Substance Misuse, Part I. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Pressbooks, pp. 287–298.

Bennett, S., Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, M., Eggins, E., and Piquero, A.R. 2018. Truancy intervention reduces crime: Results from a randomized field trial. Justice Quarterly 35(2):309–329.

Benoit-Bryan, J. 2011. The Runaway Youth Longitudinal Study. Chicago, IL: National Runway Switchboard (now called the National Runaway Safeline).

Bernburg, J.G., Krohn, M.D., and Rivera, C.J. 2006. Official labeling, criminal embeddedness, and subsequent delinquency: A longitudinal test of labeling theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 43(1):67–88.

Branscum, C., and Richards, T.N. 2022. An updated examination of the predictors of running away from foster care in the United States and trends over ten years (2010–2019). Child Abuse & Neglect, 129(2):105689.

Burr, L., Ziegler-Thayer, M., and Scala, J. 2023. Attendance Legislation in the United States. Arlington, VA: American Institutes for Research.

https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/Attendance-Legislation-in-the-US-Jan-2023.pdf

Byers, K., Barton, J., Grube, W., Wesley, J., Akin, B. A., Hermesch, E., Felzke, E., and Roosevelt, R. 2024. "I ran to make a point": Predicting and preventing youth runaway from foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 41(6):807–830.

Campbell, T., and van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. 2023. Conversion therapy, suicidality, and running away: An analysis of transgender youth in the US. Journal of Health Economics 89:102750.

Canfield, J.P., Nolan, J., Harley, D., Hardy, A., and Elliott, W. 2016. Using a person-centered approach to examine the impact of homelessness on school absences. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 33:199–205.

Castillo, B., Schulenberg, J., Grogan‐Kaylor, A., and Toro, P.A. 2023. The prevalence and correlates of running away among adolescents in the United States. Journal of Community Psychology 51(5):1860–1875.

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023a. High school YRBS [Youth Risk Behavior Survey] cross tabulation of "Currently drank alcohol" by "Experienced sexual violence" by "Anyone," "United States," and "2023." Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) Analysis Tool. https://yrbs-analysis.cdc.gov/

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023b. High school YRBS [Youth Risk Behavior Survey] cross tabulation of "Currently drank alcohol" by "Reported that their parents or other adults in their family sometimes, rarely, or never know where they are going or with whom they will be," "United States," and "2023." Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) Analysis Tool. https://yrbs-analysis.cdc.gov/

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023c. High school YRBS [Youth Risk Behavior Survey] cross tabulation of "Ever lived with a parent or guardian who had severe depression, anxiety, or another mental illness, or was suicidal" by "Currently drank alcohol," "United States," and "2023." Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) Analysis Tool. https://yrbs-analysis.cdc.gov/

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023d (April 28). Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72(1):84–92.

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024 (July 19). "Alcohol Behaviors and Academic Grades." www.cdc.gov/healthy-schools/health-academics/alcohol-and-grades.html#print

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2025 (Jan. 14). "About Underage Drinking." www.cdc.gov/alcohol/underage-drinking/index.html

Chaffin, M., Silovsky, J.F., Funderburk, B., Valle, L.A., Brestan, E.V., Balachova, T., Jackson, S., Lensgraf, J., and Bonner, B.L. 2004. Parent-child interaction therapy with physically abusive parents: Efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72(3):500–510.

Chen, X., Thrane, L., and Adams, M. 2012. Precursors of running away during adolescence: Do peers matter? Journal of Research on Adolescence 22(3):487–497.

(CJJ) Coalition for Juvenile Justice. 2013. National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged With Status Offenses. Washington, DC.

Connell, A.M., Dishion, T.J., Yasui, M., and Kavanagh, K. 2007. An adaptive approach to family intervention: Linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 75(4):568–579.

Courtney, M.E., and Zinn, A. 2009. Predictors of running away from out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review 31(12):1298–1306.

Crosland, K., Joseph, R., Slattery, L., Hodges, S., and Dunlap, G. 2018. Why youth run: Assessing run function to stabilize foster care placement. Children and Youth Services Review 85(C):35–42.

Crum, J.D., and Ramey, D.M. 2023. Impact of extralegal and community factors on police officers' decision to book arrests for minor offenses. American Journal of Criminal Justice 48(3):572–601.

(CSG) The Council of State Governments Justice Center. 2024. Support or Court: How States Respond to Youth Who Commit Status Offenses and Children Who Break the Law. New York, NY. https://projects.csgjusticecenter.org/support-or-court/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2024/06/Support-or-Court_Status-Offenses.pdf

Cullen, F.T., and Jonson, C.L. 2014. Labeling theory and correctional rehabilitation: Beyond unanticipated consequences. In Labeling Theory: Empirical Tests, edited by D.P. Farrington and J. Murray. Vol. 18 of Advances in Criminological Theory, edited by F. Adler, W.S. Lauter, and F.T. Cullen. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, pp. 63–88.

Davies, B.R., and Allen, N.B. 2017. Trauma and homelessness in youth: Psychopathology and intervention. Clinical Psychology Review 54:17–28.

DeGarmo, D.S., Eddy, J.M., Reid, J.B., and Fetrow, R.A. 2009. Evaluating mediators of the impact of the Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT) multimodal preventive intervention on substance use initiation and growth across adolescence. Prevention Science 10(3):208–220.

DiMarco, B. 2024 (March 12). Legislative tracker: 2024 State student-absenteeism bills.

https://www.future-ed.org/legislative-tracker-2024-state-student-absenteeism-bills/

Dir, A.L., Magee, L.A., Clifton, R.L., Ouyang, F., Tu, W., Wiehe, S.E., and Aalsma, M.C. 2021. The point of diminishing returns in juvenile probation: Probation requirements and risk of technical probation violations among first-time probation-involved youth. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 27(2):283–310.

Dishion, T.J., Kavanagh, K., Schneiger, A., Nelson, S., and Kaufman, N.K. 2002. Preventing early adolescent substance use: A family-centered strategy for the public middle school. Prevention Science 3(3):191–201.

Donovan, J.E. 2004. Adolescent alcohol initiation: A review of psychosocial risk factors. Journal of Adolescent Health 35(6):529.e7–18.

Donovan, J.E., and Molina, B.S. 2011. Childhood risk factors for early-onset drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 72(5):741–751.

(DSG) Development Services Group, Inc. 2017. Diversion Programs. Model Programs Implementation Guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://www.ojjdp.gov/mpg-iguides/topics/diversion-programs/

Finning, K., Ukoumunne, O.C., Ford, T., Danielsson-Waters, E., Shaw, L., De Jager, I.R., Stentiford, L., and Moore, D.A. 2019. The association between child and adolescent depression and poor attendance at school: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 245:928–938.

Goldstein, D. 2015 (March 6). Inexcusable absences. The Marshall Project. www.themarshallproject.org/2015/03/06/inexcusable-absences

Gray, L. 2023. "An Historic Analysis of the Operation of a Truancy Court Conducted in an Urban Middle School." Doctoral dissertation. St. Louis, MO: Lindenwood University.

Grube, J.W., DeJong, W., DeJong, M., Lipperman-Kreda, S., and Krevor, B.S. 2018. Effects of a responsible retailing mystery shop intervention on age verification by servers and clerks in alcohol outlets: A cluster randomized cross-over trial. Drug and Alcohol Review 37(6):774–781.

Gubbels, J., van der Put, C.E., and Assink, M. 2019. Risk factors for school absenteeism and dropout: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48:1637–1667.

Harding, F.M., Hingson, R.W., Klitzner, M., Mosher, J.F., Brown, J., Vincent, R.M., Dahl, E., and Cannon, C.L. 2016. Underage drinking: A review of trends and prevention strategies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 51(4):S148–S157.

Harris, C.B. 2021. Miami-Dade County status offenders: A literature review of punishment and rehabilitation of youth. Contemporary Issues in Juvenile Justice 11(1):1–22.

Hendricks, M.A., Sale, E.W., Evans, C.J., McKinley, L., and DeLozier Carter, S. 2010. Evaluation of a truancy court intervention in four middle schools. Psychology in the Schools 47(2):173–183.

Henry, K.L. 2007. Who's skipping school: Characteristics of truants in 8th and 10th grade. Journal of School Health 77(1):29–35.

Henry, K.L., and Huizinga, D.H. 2007. School-related risk and protective factors associated with truancy among urban youth placed at risk. The Journal of Primary Prevention 28(6):505–519.

Hockenberry, S., and Puzzanchera, C. 2024a. Juvenile Court Statistics 2021. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Hockenberry, S., and Puzzanchera, C. 2024b. Juvenile Court Statistics 2022. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Holliday, S.B., Edelen, M.O., and Tucker, J.S. 2017. Family functioning and predictors of runaway behavior among at-risk youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 34(3):247–258.

Hunt, M.K., and Hopko, D.R. 2009. Predicting high school truancy among students in the Appalachian South. The Journal of Primary Prevention 30(5):549–567.

Ingel, S.N., Drazdowski, T.K., Rudes, D.S., McCart, M.R., Chapman, J.E., Taxman, F.S., and Sheidow, A.J. 2022. Juvenile probation officers’ perceptions of sanctions and incentives as compliance strategies. Journal of Applied Juvenile Justice Services 2022:27–41.

Jafarian, M., and Ananthakrishnan, V. 2017. Just Kids: When Misbehaving Is a Crime. Brooklyn, NY: Vera. https://www.vera.org/when-misbehaving-is-a-crime#:~:text=/5YYK%2D6NNB.-,Misbehaving%20while%20under%20probation%20supervision,the%20justice%20system%20for%20misbehaving.

Javdani, S., and Daneau, N.S. 2020. Reducing Crime for Girls in the Juvenile Justice System Through Researcher-Practitioner Partnerships. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

Jennings, W.G. 2011. Sex disaggregated trajectories of status offenders: Does CINS/FINS status prevent male and female youth from becoming labeled delinquent? American Journal of Criminal Justice 36:177–187.

Jennings, W.G., Gibson, C., and Lanza-Kaduce, L. 2009. Why not let kids be kids? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between alternative rationales for managing status offending and youths’ self-concepts. American Journal of Criminal Justice 34(3):198–212.

Kendall, J.R., and Hawke, C. 2007. Juvenile status offenses: Treatment and early intervention. Technical Assistance Bulletin 29:1–12. Chicago, IL: American Bar Association, Division for Public Education.

(JJGPS) Juvenile Justice Geography, Policy, Practice, & Statistics. 2015. "Status Offense Issues." Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice. http://www.jjgps.org/status-offense-issues

Kerr, J., and Finlay, J. 2006. Youth Running From Residential Care: "The Push" and "The Pull." Province of Ontario, Canada: Office of Child and Family Service Advocacy.

Kim, B.K.E., Quinn, C.R., Logan-Greene, P., DiClemente, R., and Voisin, D. 2020. A longitudinal examination of African American adolescent females detained for status offense. Children and Youth Services Review, 108:104648.

Kim, M.J., Tajima, E.A., Herrenkohl, T.I., and Huang, B. 2009. Early child maltreatment, runaway youths, and risk of delinquency and victimization in adolescence: A mediational model. Social Work Research 33(1):19–28.

Klein, M., Sosu, E.M., and Dare, S. 2020. Mapping inequalities in school attendance: The relationship between dimensions of socioeconomic status and forms of school absence. Children and Youth Services Review, 118:105432.

Klima, T., Miller, M., and Nunlist, C. 2009. Targeted Truancy and Dropout Programs in Middle and High School. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy, Document No. 09–06–2201. http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/rptfiles/09-06-2201.pdf

Korecky, A. 2016. Curfew must not ring tonight: Judicial confusion and misperception of juvenile curfew laws. Capital University Law Review 44(4):831–872.

Krevor, B.S., Grube, J., and DeJong, W. 2017. Mystery Shop Programs to Reduce Underage Alcohol Sales. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

Kroska, A., Lee, J.D., Carr, N.T. 2017. Juvenile delinquency and self‐sentiments: Exploring a labeling theory proposition. Social Science Quarterly 98(1):73–88.

Latimore, A.D., Salisbury-Afshar, E., Duff, N., Freiling, E., Kellett, B., Sullenger, R.D., and Salman, A. 2023. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of substance use disorders through socioecological strategies. National Academy of Medicine Perspectives 2023: 10.31478/202309b.

(LDF) Legal Defense Fund. 2021 (April 22). "Supreme Court Rules Trial Courts Not Required to Make a Finding of Permanent Incorrigibility Before Sentencing Underaged Youth to Life Without Parole." New York, NY. www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021-04-22-Jones-Unfavorable-FINAL.pdf

Leung, R.K., Toumbourou, J.W., and Hemphill, S.A. 2014. The effect of peer influence and selection processes on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Health Psychology Review 8(4):426-457.

Lipsey, M.W. 2009. The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile offenders: A meta-analytic overview. Victims and Offenders 4:124–147.

Loor, K.J.P. 2019. When protest is the disaster: Constitutional implications of state and local emergency power. Seattle University Law Review 43:1–70.

Love, J.R., and Fox, R.A. 2019. Home-based parent-child therapy for young traumatized children living in poverty: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 12(1):73–83.

Lowery, P.G. 2021. The impact of race, sex, and structured activities on the intake and adjudication processes of status offenders. Journal of Crime and Justice 44(3):332–352.

MacPherson, L., Magidson, J.F., Reynolds, E.K., Kahler, C.W., and Lejuez, C.W. 2010. Changes in sensation seeking and risk‐taking propensity predict increases in alcohol use among early adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 34(8):1400–1408.

Matsumoto, C. 2020. "Permanently incorrigible" is a patently ineffective standard: Reforming the administration of juvenile life without parole. George Washington Law Review 88(1):239–268.

Maynard, B.R., McCrea, K.T., Pigott, T.D., and Kelly, M.S. 2012. Indicated truancy interventions: Effects on school attendance among chronic truant students. Campbell Systematic Reviews 8(1):1–84. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.4073/csr.2012.10

Maynard, B.R., Vaughn, M.G., Nelson, E.J., Salas-Wright, C.P., Heyne, D.A., and Kremer, K.P. 2017. Truancy in the United States: Examining temporal trends and correlates by race, age, and gender. Children and Youth Services Review 81:188–196.

Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., and Eggins, E. 2017. Reducing truancy and fostering a willingness to attend school: Results from a randomized trial of a police-school partnership program. Prevention Science 18(4):469–480.

McNeely, C.A., Lee, W.F., Rosenbaum, J.E., Alemu, B., and Renner, L.M. 2019. Long-term effects of truancy diversion on school attendance: A quasi-experimental study with linked administrative data. Prevention Science 20(7):996–1008.

McNeely, C.A., Alemu, B., Lee, W.F., and West, I. 2021. Exploring an unexamined source of racial disparities in juvenile court involvement: Unexcused absenteeism policies in U.S. schools. AERA Open 7(1):1–17.

Milligan, S. 2024 (July 3). Getting back to class: How states are addressing chronic absenteeism. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures.

www.ncsl.org/state-legislatures-news/details/getting-back-to-class-how-states-are-addressing-chronic-absenteeism

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. 2009. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities, edited by M.E. O’Connell, T. Boat, and K.E. Warner. Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Runaway Safeline. 2021. Let's Talk: Runaway Prevention Curriculum.

https://cdn.1800runaway.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/RPC-Evidence-Based-Paper-English-FY16.pdf

(NCJFCJ) National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. 2019. Resolution in Support of Reauthorization and Strengthening of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act and Elimination of the Valid Court Order Exception. Adopted by the NCJFCJ Board of Directors July 15, 2017. Washington, DC.