Youth curfews are an example of a local policy response to crime and delinquency committed by youths or to an increase in incidents of victimization of youths. While the requirements and restrictions vary by time, place, and age (Hazen and Brank, 2018), the general concept is that keeping youths at home during the late-night to early morning hours will limit their opportunities to commit or become victims of crime (Carr and Doleac, 2018) and thus will enhance public safety.

This literature review examines youth curfews by providing definitions of curfew laws or ordinances, discussing their intended goals and how they are applied locally, and providing detailed data on youth violations of curfews and the consequences of this offense. It provides a historical background on the use of curfews, constitutional challenges that have been argued, and disparities in enforcement. It summarizes the research on the effectiveness of curfews in improving public safety, reducing delinquent activity and victimization, and maintaining parental authority. It also discusses gaps in research. The review concentrates primarily on nighttime curfews for youth, and not on curfews for the general population.

This section defines the terms related to youth curfews and the juvenile justice system mechanisms that can be used when curfews are violated.

Curfews are regulations that prohibit members of a certain population from being in public during a specified time (Hazen and Brank, 2018). Youth curfew laws or youth curfew ordinances (sometimes referred to as “curfew statutes”) prohibit youths under certain ages from being in public places during certain times (Wilson et al., 2016; Stoddard et al., 2015; Korecky, 2016). While the age cutoff for youth curfews may vary at the local level, for the purposes of this review juveniles are defined as the population of individuals under age 18 with the potential for or actual contact with the juvenile justice system; youth refers to the general population of individuals under 18.

For the purposes of this review, a curfew violation is defined as an individual “being found in a public place after a specified hour of the evening, usually established in a local ordinance applying only to persons under a specified age” (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:99). A curfew violation is considered a status offense, which is an act that is illegal only because the person committing it is of juvenile status (DSG, 2015; Puzzanchera, Hockenberry, and Sickmund, 2022; Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2023). A status offense differs from a delinquent offense, which is defined as an act committed by a juvenile for which an adult could be prosecuted in criminal court (Puzzanchera, Hockenberry, and Sickmund, 2022). For more information, visit the Model Programs Guide (MPG) literature review on Status Offenders.

This literature review summarizes the research on youth-specific nighttime curfew laws to improve public safety, reduce delinquent activity and victimization, and maintain parental authority. However, there are other types of curfew laws and restrictions, which have different purposes.

- Daytime curfew laws may be used for truancy enforcement and are intended to improve school attendance (Adams, 2003; Adams, 2007; Wilson et al., 2016).

- Emergency curfews are implemented for brief periods for individuals of all ages, in the interest of public safety, often during state-of-emergency declarations (Apel, Rohde, and Marcus, 2023; Loor, 2019; Norton, 2013). For example, emergency curfews were enacted in 2020 to slow the spread of the COVID–19 virus (Apel, Rohde, and Marcus, 2023) and have been used at the state and local level in response to mass protests (Loor, 2019; Ugwu, 2022).

- Curfew ordinances may be in place to restrict specific activities for youth, such as driving after a certain hour of night (Wilson et al., 2016; Adams, 2003).

- Curfews also can be used as a condition of probation in delinquency cases or as part of a diversion agreement (Puzzanchera, Hockenberry, and Sickmund, 2022; SBB, 2023d). For more information about curfews used for youths placed on probation, see the MPG literature review Formal, Post-Adjudication Juvenile Probation Services.

Most youth curfews laws are enacted to improve public safety and maintain order, with the goal of reducing delinquency and criminal activity by keeping individuals indoors who may commit crimes in public spaces (Carr and Doleac, 2018; Hazen and Brank, 2018; Norton, 2013; Wilson et al., 2016). These laws also are intended to prevent youth victimization and to maintain parental authority (Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016; Stoddard et al., 2015; Norton, 2013). Supporters of youth curfew laws also posit that they may help law enforcement identify youths at high risk of offending, since youths who are out after curfew are more likely to have ineffective supervision (Hazen and Brank, 2018).

Communities with youth curfew laws or ordinances may apply them to all youths under age 18, while some localities apply curfews to individuals 16 and under or 17 and under (Adams, 2007; Wilson et al., 2016). The restricted hours differ by location, but they are enforced generally during late evening to early morning hours—for example 10 p.m. or 11 p.m. to 6 a.m. (Wilson et al., 2016; Yeide, 2009; Puzzanchera, Hockenberry, and Sickmund, 2022).

Generally, if youths are found violating curfew, they are taken into police custody and released to their parents (Carr and Doleac, 2018). Other consequences for violating curfew may vary by location but can include fines, community service, driver’s license restrictions, and, on rare occasions, detention (Wilson et al., 2016; Carr and Doleac, 2018; Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2023). Parents who violate the curfew law by allowing their child to be in public during curfew hours can be subjected to fines (Carr and Doleac, 2018). Exceptions to general youth curfew ordinances sometimes are made if the youth is going to or from their place of employment, accompanying a parent, attending a religious event, or exercising their right to free speech (Carr and Doleac, 2018; Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2015; Korecky, 2016).

Historical Use, Scope, and Examples of Youth Curfews

Curfews typically are enacted by cities or towns, though sometimes by counties or states (Hazen and Brank, 2018; Loor, 2019; National Youth Rights Association, 2024), usually in response to increased incidents of crime and delinquency committed by youths and/or increased incidents of victimization of youths (Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016). In 1880, Omaha, NE, enacted the first youth curfew (Hemmens and Bennett, 1999; Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016). The earliest curfews required children to be home by sunset (Buck, 1897; Diviaio, 2007). Since then, the number of jurisdictions with youth curfew laws has fluctuated. Despite legal challenges to city-implemented youth curfew laws (see Legal Challenges of Youth Curfews), curfew ordinances are in effect in most of the nation’s largest cities (Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016). In 2023, more than a dozen cities and counties enacted new youth curfew laws or reinstated or enforced previously established youth curfew laws in response to growing public concern over crime and delinquency, including Fulton County, GA; Memphis, TN; New Smyrna Beach, FL; Ocean City, Sea Isle City, and Wildwood, NJ; and Washington, DC (Hernández, 2023; Ugwu, 2022). By 2024, almost every U.S. state had one or more cities or counties with a youth curfew law (National Youth Rights Association, 2024).

For example, in 2014 Baltimore, MD, revised an existing youth curfew statute due to an increase in the number and seriousness of crimes committed by youth. The goals were to reduce delinquency and promote education (for example, improve youths' school attendance and other education outcomes) [Baltimore City Department of Legislative Reference, 2022; Middleman, 2015]. Under the revised curfew, youths ages 14–17 are prohibited from being out of their homes past 10 p.m. on a weeknight (11 p.m. during the summer) or 11 p.m. on a weekend (previously, youths were permitted to remain in public until 11 p.m. on weeknights and midnight on weekends) [Wallace, 2020; Baltimore City Department of Legislative Reference, 2022]. Baltimore's revised nighttime curfew does not apply to youths accompanied by a parent, going to an official school or religious event, going to or returning from employment, or exercising First Amendment rights such as the free exercise of religion or speech (Baltimore City Department of Legislative Reference, 2022). In Washington, DC, curfew hours apply to anyone under 17 and are from 11 p.m. to 6 a.m. on Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday nights, and from 12:01 a.m. to 6 a.m. on Saturday and Sunday, except during July and August, when curfew hours are 12:01 a.m. to 6 a.m. every night (Carr and Doleac, 2018). In 2023, Washington, DC, launched an Enhanced Juvenile Curfew Enforcement Pilot where Metropolitan Police Department officers bring youth (under age 17) in seven target areas who are in violation of the curfew to the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services, instead of remaining with them at the station. This allows officers to return to patrol, and the youths and their families to be connected with services and support (Office of the Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice, 2023).

Theoretical Basis of Youth Curfews

Some theories support the use of curfews to reduce crime committed by youths and their victimization from crime. In this section, we describe three of the supporting theories: 1) crime opportunity, 2) routine activities, and 3) deterrence.

Crime opportunity theory is the concept that if opportunities are accessible people will take advantage of them (Campbell and Lester, 1999); that is, youths are simply less likely to commit crimes if they are not on the streets (Adams, 2003), as their opportunities to learn about and commit crime have been removed by the curfew (Cole, 2003).

Within crime opportunities is routine activities theory, which provides a theoretical rationale for youth curfews and is based on the idea that crime results from people’s everyday behavior and routines (Cohen and Felson, 1979). Within this theory, individuals make rational choices about committing crime, and for crime to occur, three elements must be present: 1) an individual motivated to commit the crime, 2) a suitable target, and 3) the absence of capable guardians. The theory suggests that youth curfews would reduce crime by restricting the hours during which youths can be in public, thereby reducing the number of youths motivated to commit offenses and the number of youths who could be targeted and victimized frequenting public spaces during specified hours (Wallace, 2020; Wilson et al., 2016). Similarly, by prohibiting youths from being unsupervised in public places after certain hours, youth curfews would be expected to reduce crime by limiting situations where guardians are absent (Wallace, 2020; Wilson et al., 2016).

Deterrence is another theory supporting the use of youth curfews, as the potential for fines or other consequences of curfew violation may deter youths from being out in a public place during curfew hours (Wilson et al., 2016). Deterrence theory specifically supports the use of curfews for public safety, positing that the threat of being stopped by police may act as a deterrent to some delinquent behavior (Stoddard et al., 2015). Further, this theory also supports the use of curfews for juveniles on probation; essentially, when youths are aware of the consequences from failure to obey curfew, they will be deterred from staying out on the street (Urban, 2005).

This section provides data on juvenile arrests and juvenile court petitions for curfew law violations. Notably, 2020 was the onset of the COVID–19 pandemic, which may have affected policies, procedures, and data collection activities regarding referrals to and processing of youth by juvenile courts and the volume and type of law-violating behavior that came to the attention of law enforcement for an indeterminate period (SBB, 2023a; SBB, 2022).

Juvenile Arrests

National arrest data combine curfew violations with loitering violations, owing to how data are reported to the FBI (SBB, 2022). Arrest rates of persons ages 10–17 for loitering and curfew violations peaked in the late 1990s, when the arrest rates were more than 500 per 100,000 youths, and have decreased steadily since then. Since 2013 the yearly arrest rates for persons ages 10–17 for loitering and curfew violations have not surpassed 160 per 100,000; in 2019 the arrest rate was 43.9 per 100,000; and in 2020 the arrest rate was 35 per 100,000 (SBB, 2022). From 1996 to 2020, the arrest rate of this population for loitering and curfew violations decreased by 94 percent (from 593.9 to 35.0 per 100,000).

The male arrest rate for loitering and curfew violations has been consistently higher than the female arrest rate since at least 1980. The male rate was at least three times as large as the female rate from 1980 through 1984. For example, in 1981, the male arrest rate for curfew violations and loitering was 477.1 per 100,000 while the female rate was 137.6 per 100,000—nearly 3.5 times as large. This disproportionality decreased steadily from 1981 until the late 2000s, when the male rate was 2.1 times as large as the female rate. The disproportionality increased slightly between 2010 and 2014, then fell steadily until 2020, when the male arrest rate was 1.8 times the females arrest rate (45.1 per 100,000 and 25.4 per 100,000, respectively) [SBB, 2022].

Juvenile Court Petitions

A youth charged with a status offense—which includes curfew violations—may be referred to juvenile court, where decisions are made whether to process the individual formally with the filing of a petition. For curfew violation cases, law enforcement agencies are the primary source of referrals to juvenile court (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). In many localities, agencies other than juvenile courts (including family crises units and social service agencies) process status offense cases. These cases are excluded from the data discussed in this section.

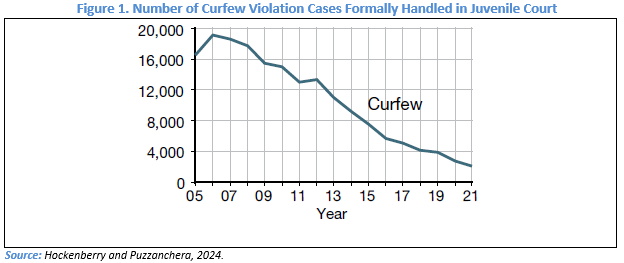

In 2021, juvenile courts handled about 2,100 petitioned curfew violation cases, which reflects a decrease of 89 percent from 2006, when more than 19,000 youths were petitioned in juvenile court with curfew violations (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:64) [see Figure 1]. Historically, fewer youths are petitioned for curfew violations than for the other four status offenses; this was also the case in 2021 when there were 29,600 petitioned truancy cases, 6,100 runaway cases, 5,600 liquor law violation cases, and 4,600 ungovernability cases (compared with 2,100 petitioned curfew violation cases). In other words, curfew violations accounted for only 4 percent of all petitioned status offense cases in 2021, which was the lowest rate of all the status offense categories (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024).

Of the 2,100 petitioned curfew violation cases in 2021, 57 percent involved youths under age 16. Also, 54 percent involved white youths, 30 percent involved Black youths, 11 percent involved Hispanic youths, 3 percent involved Asian youths, and 2 percent involved American Indian youths (SBB, 2023c). Between 2005 and 2021, the number of petitioned curfew violation cases declined 88 percent for white youths, 87 percent for Black youths, 85 percent for Hispanic youths, 78 percent for Asian youths, and 92 percent for American Indian youths (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). For more information about race, see Racial Disparities Related to Youth Curfew Laws.

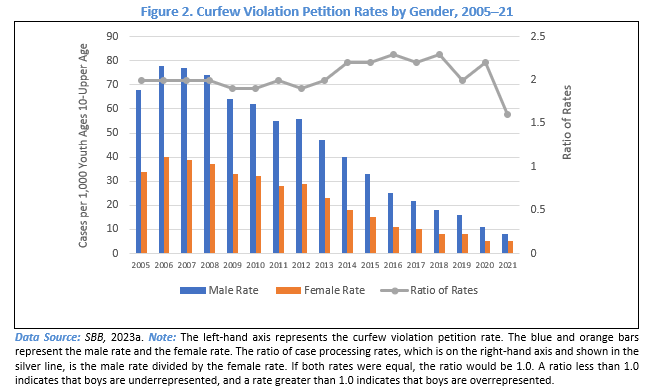

As with the gender differences at arrest, there are large gender differences related to juvenile court cases for curfew violations. First, boys are overrepresented among the youths petitioned in juvenile court. In 2021, boys accounted for the majority (65 percent) of petitioned curfew violation cases while girls accounted for 35 percent of the cases (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:68; SBB, 2023c). The male curfew violation petition rate was 8 per 100,000 in 2021, compared with 5 for girls (see Figure 2). Between 2005 and 2020, the male curfew violation case rate was about twice as large as the female case rate, and in 2021 the male rate was 60 percent greater than the female rate (SBB, 2023a). Second, a smaller percentage of girls are represented among curfew violation cases (35 percent in 2021), compared with the other four status offenses, where girls accounted for between 43 percent and 56 percent of the cases petitioned in juvenile court in 2021 (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024; SBB, 2023c). Third, the age when curfew violation petitions peak differs by gender: rates peaked at age 15 for females and 16 for males in 2021 (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). For more information, see the MPG literature review on Girls in the Juvenile Justice System.

Youths charged with status offenses are sometimes held in secure detention while their cases are being processed (defined in this context as “the placement of youth in a secure facility under court authority at some point between the time of referral to court intake and case disposition” [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:95]). Between 2005 and 2021, the number of curfew cases that involved secure detention decreased substantially from at least 2,000 yearly in 2005–07 to fewer than 100 in 2021. Between 2005 and 2021, the number of petitioned curfew cases that involved detention decreased by 97 percent. This was greater than the decrease in the other four status offenses (the number of detentions for liquor law violation cases decreased by 92 percent, detentions for truancy cases decreased 86 percent, detentions for ungovernability cases decreased 85 percent, and detention for runaway cases decreased 83 percent) [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:77]. The percentage of petitioned curfew cases that involved secure detention also decreased during this period, from more than 10 percent of cases during 2005–09 to fewer than 5 percent during 2019–21 (SBB, 2023e). For more information, see the MPG literature reviews on Juvenile Residential Programs and Alternatives to Detention and Confinement.

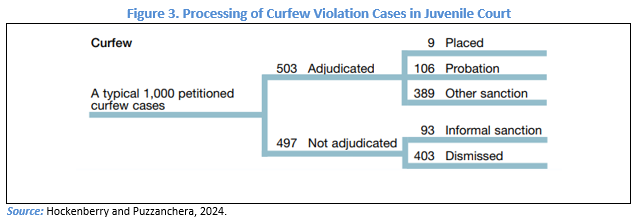

Juvenile courts may adjudicate petitioned curfew violation cases and can order various sanctions such as probation or out-of-home placement (here, "adjudicated" refers to the judicial determination that the youth was responsible for the offense [Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024]). Between 2005 and 2021, the number of cases in which youths were adjudicated for a status offense decreased 90 percent for curfew violations (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024). In 2021, among all status offense categories, adjudication was most likely in cases involving curfew violations: 50.0 percent of petitioned curfew cases were adjudicated, compared with 45.2 percent of ungovernability cases, 45.0 percent of liquor law violation cases, 32.6 percent of truancy cases, and 25.6 percent of runaway cases.

However, because of the small numbers of youths with curfew violation cases in juvenile court, curfew violations in 2021 represented only 6 percent of all adjudicated status offense cases. Further, of petitioned curfew violation cases that were adjudicated in 2021, 50 percent involved youths ages 15 or younger, 49 percent involved males, 63 percent involved white youths, and 26 percent involved Black youths (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024).

Figure 3 demonstrates the processing of curfew violations in juvenile court in 2021. Fewer than 2 percent of adjudicated curfew violation cases resulted in an out-of-home placement disposition, 21 percent of cases resulted in probation, and 77 percent resulted in other sanctions such as restitution, community service, paying a fine, or referral to treatment or counseling programs.

Racial disparities in the juvenile justice system are well documented (see the MPG literature review on Racial and Ethnic Disparity in Juvenile Justice Processing). Similarly, researchers have identified racial disparities in the enforcement of youth curfew laws, finding they consistently disadvantage Black youths. Other racial and ethnic groups also are disadvantaged, including American Indian youths. Although arrest and juvenile court petition rates have decreased substantially for all races, racial disparities still existed through at least 2021.

In 2020 the arrest rate for curfew and loitering violations was 33.1 for white youths, 53.3 for Black youths, 48.9 for American Indian youths, and 7.7 for Asian youths (as mentioned above, juvenile curfew and loitering violation arrests are combined) [SBB, 2022]. Hispanic youths are included in those racial groups (and not counted as a separate race/ethnicity). These rates have declined drastically since peaking in the late 1990s. However, since at least 1980, the Black arrest rate for curfew and loitering violations has been greater than the white arrest rates. This disparity peaked between 2012 and 2018, when the Black arrest rate was at least three times as great as the white arrest rate.

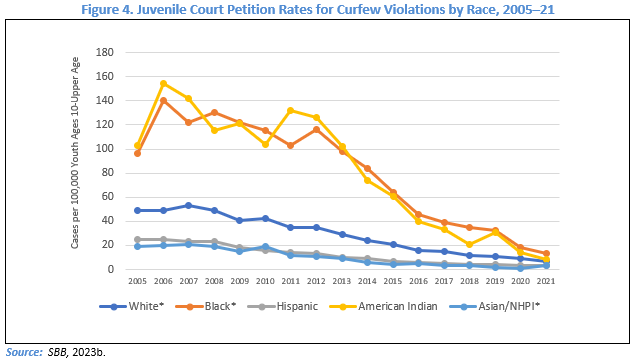

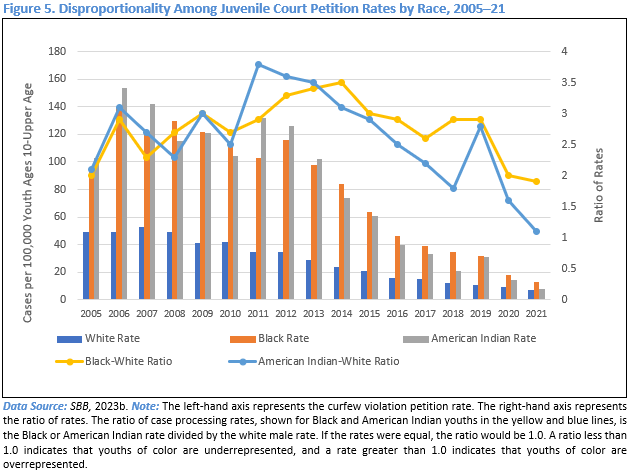

There also are racial disparities in juvenile court petitions. In 2021, for every 100,000 white juveniles in the population, there were 7 curfew violation petitions filed in juvenile court. The rate was 13 per 100,000 for Black juveniles, 8 per 100,000 for American Indian juveniles, 3 per 100,000 for Hispanic juveniles, and 3 per 100,000 for Asian juveniles (SBB, 2023b) [see Figure 4]. Since 2007, the curfew violation rates for Hispanic juveniles and Asian juveniles have been less than half the rate for white juveniles. However, the rates for both Black and American Indian juveniles have been higher than the rate for white youths during each of these years. For example, the Black rate has been about two to three-and-a-half times as high as the white rate for at least the past 17 years (see Figure 5).

Researchers and advocates have attempted to identify and assess the contributing factors to racial disparities in juvenile curfew law violations (e.g., Norton, 2013; Sutphen and Ford, 2001; Ugwu, 2022). Several articles examine the historical context of curfew laws, starting with laws imposed on free and enslaved Black people of all ages during slavery that restricted their movement (Ugwu, 2022; Norton, 2013). After the abolishment of slavery, ordinances known as “sundown town” laws restricted the movement of Black individuals in white communities to the hours between sunrise and sunset (Ugwu, 2022; Norton, 2013).

Additionally, while many curfews are citywide, some curfews are limited to hot spots—or areas of the city where there is a high concentration of crime (Norton, 2013; Ruefle and Reynolds, 1995). These areas also happen to be where most Black and Brown youths reside, which means they are more likely to be affected by these laws (Norton, 2013). This contributing factor to racial disparities in the juvenile justice system sometimes is called justice by geography (Leiber, Richetelli, and Feyerherm, 2009; Pupo and Zane, 2021), described as when youths of color live in jurisdictions that have stricter law enforcement or harsher judges, compared with jurisdictions where white youths live (Bray, Sample, and Kempf–Leonard, 2005; Leiber, Richetelli, and Feyerherm, 2009; Taylor et al., 2012).

Empirical studies have shown that youths of color are disproportionately affected by youth curfew enforcement (Ugwu, 2022). A study examining the effect of a teen curfew on a city with a population of more than 200,000 showed that more curfew violations were issued in areas with higher rates of juvenile arrests, higher levels of police presence, and lower family incomes (Sutphen and Ford, 2001). Similarly, parental citations were highest in areas with lower family incomes and greater proportions of Black populations (Sutphen and Ford, 2001).

Opponents have argued these laws violate several rights, including the rights to free assembly and freedom of speech and religion (Norton, 2013); protection against unreasonable search and seizure (OJJDP, 1996); the right of movement (Grossman and Hoke, 2015); protection from self-incrimination (Quinn et al., 2022); due process by being overly vague (Quinn et al., 2022), and the right to privacy and family autonomy (Quinn et al., 2022). Numerous legal challenges to the constitutionality of curfew laws have been made in state and federal courts, though none have been heard by the U.S. Supreme Court (LeBoeuf, 1996). Thus, substantial variation exists in both the legal standards by which to assess the laws (Stoddard et al., 2015) and the legal determinations. For example:

- Bykofsky v. Borough of Middletown (401 F. Supp. 1242, M.D. PA, 1975) was the first federal case (U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania) that challenged juvenile curfew laws (Diviaio, 2007; Harvard Law Review, 2005). In that case, a mother, on behalf of herself and her son, challenged the curfew ordinance of the borough of Middletown, PA, on the grounds that the ordinance 1) was unconstitutionally vague; 2) violated due process rights of minors, specifically, their right to freedom of movement; 3) violated minors’ rights to freedom of speech, freedom of association, and freedom of assembly; 4) violated the fundamental right to interstate travel; 5) violated the constitutional right to intrastate travel; 6) interfered with the right of parents to direct the upbringing of their children and violated the right to family autonomy; and 7) violated the constitutional right to equal protection under the law. The court upheld the curfew ordinance and ruled in favor of the borough of Middletown. Although the court ruled that most of the curfew statute was constitutional, it did require the removal of a few sections of the law that were stricken because of vagueness (Bykofsky v. Borough of Middletown, 1975).

- In 1991, several parents filed a lawsuit against the city of Dallas, TX, to strike down the curfew ordinance, claiming it took away their right to control their children and set curfews of their own (Diviaio, 2007; Qutb v. Strauss, 1993). The ordinance made it a misdemeanor for persons under age 17 to use the city streets or to be present at other public places within the city from 11 p.m. until 6 a.m. during weekdays and from midnight to 6 a.m. on weekends (Diviaio, 2007). The Dallas ordinance allowed several exceptions to the curfew, such as being accompanied by a parent or guardian, coming home from work, or carrying a note from one’s parents and attending school-, religious-, or First Amendment–related activities (LeBoeuf, 1996). The district court ruled for the parents, but in Qutb v. Strauss (1993) the Fifth Circuit reversed the decision, ruling that the curfew did not impermissibly impinge on the parent’s rights and thus did not violate the Constitutions of the United States and Texas (Qutb v. Strauss, 1993). After surviving constitutional scrutiny, the Dallas curfew became a model for many other U.S. cities (LeBoeuf, 1996; Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016). Today, Dallas imposes a nighttime curfew year-round and a daytime curfew during school hours.

- The plaintiffs in Ramos v. Town of Vernon (2003) argued that the youth curfews imposed by their communities on individuals under 18 years of age violated their Fourth Amendment rights because the curfews 1) exposed the minors to unreasonable stopping and detainment by law enforcement, 2) prevented them from enjoying the same protections as adults solely because they were minors, and 3) if imposed on adults, would violate their right to intrastate travel, and therefore, should not be imposed on minors (Ramos v. Town of Vernon, 2003). However, the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut determined that the ordinance did not violate the U.S. Constitution (Ramos v. Town of Vernon, 2003). The United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit later reversed the district court's judgment and ruled the curfew unconstitutional, stating that the town of Vernon ordinance infringed on the equal protection rights of minors (353 F.3d 171).

- In City of Sumner v. Walsh (2003), after being fined for his 14-year-old son’s curfew violations, Thomas Walsh argued that the curfew ordinance of Sumner, WA, was unconstitutional because it violated the right of minors to move freely in public places, violated the right of parents to rear their children, and was vague. The curfew ordinance prohibited youths from remaining in public places after certain hours and made it illegal for the parents of youths to permit or knowingly allow them to remain in public places during curfew (City of Sumner v. Walsh, 2003). In 2003 the Washington Supreme Court overrode the decision of a lower court, which found Walsh guilty of allowing his son to violate the Sumner youth curfew ordinance. The Washington Supreme Court struck down the entire youth curfew ordinance as being unconstitutionally vague because it failed to properly define exemptions under the law (City of Sumner v. Walsh, 2003; Quinn et al., 2022; Grossman and Hoke, 2015).

Although widely enforced, youth curfew laws remain under scrutiny and are the subject of ongoing legal debate in the United States. Courts have made varying decisions regarding the legality of curfew ordinances based on constitutional and civil rights arguments. Because of the lack of conclusive decisions from the U.S. Supreme Court, lower courts must determine the constitutionality of these laws—resulting in different state laws and local ordinances (Stoddard et al., 2014).

The Impact of Youth Curfews on Crime-Related Outcomes

Youth curfew laws often are components of juvenile justice programs; however, rigorous program evaluations of their effectiveness are limited. The following program and practice, which are featured in the Model Programs Guide, provide a brief overview of how youth curfews have been implemented in programming. Overall, there is mixed evidence on the effectiveness of curfews on various youth crime outcomes, and some evidence of negative effects.

Operation Night Light (ONL) is a home-visiting program that includes a curfew for youths as a condition of their probation and a requirement of participation in the program. The curfew is enforced on the weekdays beginning at 7 p.m. for middle school students and at 8 p.m. for high school students, and on the weekends beginning at 9 p.m. for middle school students and at 11 p.m. for high school students. The curfew does not apply if the youth is accompanied by a parent or an approved guardian. Alarid and Rangel (2018) found that youths receiving ONL were less likely to successfully complete probation and more likely to have their probation revoked because of a technical violation than comparison youths on regular probation were. ONL youths also were more likely to commit a new crime during probation supervision, compared with the youths on regular probation. These differences between the groups were statistically significant. However, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the frequency of probation revocation owing to the severity of the new crime committed. Finally, youths receiving regular probation recidivated sooner than ONL youths did.

Wilson and colleagues (2016) conducted a meta-analysis to examine the overall impacts of Juvenile Curfew Laws (as opposed to curfews imposed on youths as part of a sentence or probation) on crimes committed by youths. Two of the 12 studies examined arrests of youth during curfew hours (one during nighttime curfews, one during daytime curfews), which was the outcome of interest. Wilson and colleagues (2016) found that overall curfews did not have a statistically significant effect on criminal behavior by youth during curfew hours. The authors noted, however, that the findings could also indicate that there could have been an effect that was too small to be measured.

There also are systematic reviews of youth curfew laws or ordinances that examine their impact on various outcomes (this research is not eligible for inclusion on the Model Programs Guide). Grossman and Miller (2015) conducted a systematic review to examine the effectiveness of curfew laws on youth justice outcomes. Of the eight studies examining the effectiveness of curfew laws on crimes committed by youths and youth victimization, four found evidence to suggest that youth curfew laws could lead to reductions in crime and victimization. For example, statistically significant reductions in youth arrests for burglaries, larcenies, and simple assaults were found after cities had implemented or revised existing curfew laws. However, four studies found no statistically significant effect of curfew laws, and one study found increases in youth arrests for homicides after the curfew law had been enacted (Grossman and Miller, 2015). An earlier systematic review by Adams (2003) explored the impact of youth curfews on crime, measured by police calls for service and arrest data. Across 10 studies that examined both nighttime and daytime curfews, the results were mixed; studies reported a combination of no change in crime, a decrease in crime (for example, gang-related violence), and an increase in crime after curfew implementation (including robbery, auto theft, and property victimization). Overall, the research did not demonstrate that curfews produced a decrease in crime committed by youth.

A few studies have examined the effect of changes in local youth curfew ordinances on crime committed by youths. In 2014, Baltimore, MD, revised its existing youth curfew beginning at 11 p.m. on weeknights and midnight on weekends to restrictions on youths under 14 years old from being in any public place or establishment between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. on weekdays or weekends. Baltimore’s curfew also prohibits youths ages 14–17 from staying out past 10 p.m. on weekdays (11 p.m. during the summer) and after 11 p.m. on weekends. Further, a daytime curfew is imposed during school hours. Parents or guardians of youths who violate curfew may face fines or perform mandated community service. The goals of Baltimore’s youth curfew laws are to reduce crime and victimization. Wallace (2020) examined the impact of the curfew changes on the number of arrests (using police arrest records for violent crime, property crime, public order offenses, drug-related crime, and other offenses) between January 1, 2013, and August 22, 2015. Results found that the implementation of Baltimore’s revised curfew laws was associated with a statistically significant increase in the ratio of arrests for youths to arrests for adults during curfew hours.

In Washington, DC, the youth curfew changes at certain times of year. The curfew time for anyone under 17 is 11 p.m. on weeknights and midnight on weekends from September through June, and midnight on all nights during July and August. The weekday curfew time changes from 12 a.m. to 11 p.m. on September 1 and back to 12 a.m. on July 1, in alignment with the school year. Carr and Doleac (2018) evaluated the impact of the city’s curfew law on gun violence to examine whether curfews inadvertently increased crime by removing youths who could be witnesses and bystanders from the streets. Specifically, the authors examined gun violence during the “switching hour,” or 11:00 to 11:59 p.m. on weekdays, compared with changes during two sets of control hours: the 11:00 p.m. hour on weekends (which is always before curfew), and the midnight hour (which is always after curfew). The evaluation found that the curfew law statistically significantly increased the number of ShotSpotter-detected gunfire incidents during the switching hour. However, the curfew also was associated with reductions in reported crime measures including the number of 911 calls to report gunfire.

Other research lends some support to curfews' reducing youth arrests. Kline (2012) examined youth curfew enactment in 54 U.S. cities that began enforcing curfews around the same time. Findings indicated that curfew enactment led to reductions in arrests for Uniform Crime Reporting Part 1 offenses (e.g., criminal homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, arson, and motor vehicle theft) for youths below the curfew age (typically, under age 16 or 17), but there was no statistically significant impact on arrests rates of individuals above curfew age. The enactment of curfew laws also was associated with a reduction in violent and property crimes committed by youths below the statutory curfew age (Kline, 2012).

The Impact of Youth Curfews on Health-Related Outcomes

While youth curfews generally are intended to reduce crimes committed by youths and youth victimization, and to increase public safety, they may also affect other youth outcomes. The systematic review by Grossman and Miller (2015) also examined the impact of youth nighttime curfew laws on public health outcomes. Of the six studies examining the effectiveness of youth curfew laws on measures of adverse youth health outcomes, five found a beneficial impact. This suggests that curfew laws were effective at reducing these outcomes (which included youths' driving-related injuries and fatalities, the number of out-of-hospital emergency medical system pediatric transports, and the number of youth trauma cases). However, given the limited quality and number of studies, more rigorous research is required before inferences can be made (Grossman and Miller, 2015).

Underage drinking is one behavior that might be influenced by local ordinances that restrict youths from being out during certain hours. Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller (2016) examined the effect of youth curfew laws on underage drinking for 15 years—from 1991 to 2005—using data from 46 U.S. cities, and found the laws did not statistically significantly affect youth drinking habits: specifically annual drinking, monthly drinking, and heavy episodic drinking (defined as five or more drinks in a row at least once during the past 2 weeks) [Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016].

There are several gaps in the research related to youth curfews. Most of the research on the impact of curfews on crimes committed by youths was conducted in the late 1990s and early 2000s (Hazen and Brank, 2018) or with curfew policies implemented in the 1990s, and there is need for evaluation of more modern curfew laws. Future research on youth curfews could benefit from the use of more rigorous study designs, such as randomized control trials (Adams, 2003; Wilson et al., 2016; Hazen and Brank, 2018), the evaluation of additional outcomes (Pollack and Russell, 2021), and longer series of data points to account for changing crime trends unrelated to curfew laws (Wilson et al., 2016). For example, future research could explore the effect of youth curfews on other outcomes—such as truancy, drug and alcohol use, or domestic violence—that are not often evaluated in the literature but which may be affected by youth curfew laws, and possible covariates (e.g., socioeconomic status, family stability, neighborhood crime) that may mitigate or exacerbate the effects of curfews (Pollack and Russell, 2021).

The field could also benefit from more qualitative studies on youth curfews. Many studies assessing crime-related outcomes, such as arrests for curfew violations, do not include details about the arrest, such as how the officer made contact with the youth (Hazen and Brank, 2018). An important component of examining the effectiveness of curfew laws is determining the level to which they are enforced (statewide, citywide, countywide, in hot spots, etc.) [Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016], but observing enforcement of curfews is a challenge for a few reasons. Actual enforcement of curfew laws may vary based on local priorities (Grossman, Jernigan and Miller, 2016; Wilson et al., 2016). Interest in enforcement may wane over time (Grossman, Jernigan and Miller, 2016). Further, local agencies may rely on officer discretion to enforce laws (Wallace, 2020). Future researchers should explore the utility of case studies to examine factors related to enforcement (Grossman, Jernigan and Miller, 2016). More qualitative research related to enforcement practices could provide insight into why disparities exist, as they relate to both the implementation and the impact of these laws. Additionally, further research on youth perceptions of curfews is needed. Specifically, self-report or interview-based research is lacking on parents' and youths' views on the necessity of curfews and whether youths perceive these laws as fair or unfair (Wallace, 2020). Self-report or interview-based research also could be helpful in assessing the effectiveness of curfews. Many youths break curfew without being detected by law enforcement. Since official data captures only those curfew violations reported by the police, these types of data might underreport the prevalence of curfew violations. They may also obscure racial, ethnic, or gender disparities in curfew arrest rates. This is particularly important for nighttime curfews, as violations may be less likely to go detected if not self-reported, compared with daytime curfew violations—which can be detected easily by schools and other trusted officials (Wallace, 2020).

Youth curfew violation arrest data reporting also presents challenges. Currently, law enforcement agencies report curfew and loitering law violations for persons under 18 to the FBI's Uniform Crime Reporting, as the FBI's definition combines these as one offense type (FBI, 2019b). This raises challenges in assessing the unique impact of these offenses on various youth outcomes.

Finally, there is a lack of data on the cost of enforcing curfews (Kline, 2012). Curfew proponents argue they are a low-cost public safety policy, while others argue they are an inefficient use of police resources (Korecky, 2016). Moreover, the actual cost depends on various factors of implementation, which are not always accounted for in research, such as whether the youth who violated curfew is issued a citation or taken into custody (Adams, 2003).

The purposes of youth curfew laws usually are to improve public safety, maintain order, reduce delinquency, prevent youth victimization, maintain parental authority, and identify high-risk youths who are out during curfew times (Carr and Doleac, 2018; Grossman, Jernigan, and Miller, 2016; Hazen and Brank, 2018; Norton, 2013; Stoddard et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2016). Despite legal challenges and mixed evidence of their effectiveness at the intended purposes, youth curfews continue to be a common local policy (National Youth Rights Association, 2024; Wallace, 2020). In the past few decades, the numbers of youths coming to the attention of law enforcement and the juvenile court for curfew violations have declined substantially; between 2006 and 2021 there was an 89 percent decrease in petitioned curfew violation cases handled by juvenile courts (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera, 2024:64). Future research may address the identified research gaps regarding curfews' effectiveness on crimes committed by youth; safety and well-being outcomes; disparities in implementation and enforcement; and their cost effectiveness.

Adams, K. 2003. The effectiveness of juvenile curfews at crime prevention. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 587(1):136–159.

Adams, K. 2007. Abolish juvenile curfews.Criminology & Public Policy 6(4):663–670.

Alarid, L.F., and Rangel, L.M. 2018. Completion and recidivism rates of high-risk youth on probation: Do home visits make a difference? Prison Journal 98:143–162.

Apel, J., Rohde, N., and Marcus, J. 2023. The effect of a nighttime curfew on the spread of COVID–19. Health Policy 129:1–8.

Baltimore City Department of Legislative Reference. 2022. Article 19: Police Ordinances. https://legislativereference.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/Art%2019%20-%20PoliceOrds_(rev%2004-11-22).pdf

Bray, T.M., Sample, L.L., and Kempf–Leonard, K. 2005. Justice by geography: Racial disparity and juvenile courts. In Our Children, Their Children, edited by D.F. Hawkins and K. Kempf–Leonard. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Buck, W. 1897. Objections to a children’s curfew. North American Review 164(484):381–384.

Bykofsky v. Borough of Middletown, 401 F. Supp. 1242 (M.D. PA 1975) . https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/401/1242/1604755/

Campbell, F., and Lester, D. 1999. The impact of gambling opportunities on compulsive gambling. Journal of Social Psychology 139:126–127.

Carr, J.B., and Doleac, J.L. 2018. Keep the kids inside? Juvenile curfews and urban gun violence. Review of Economics and Statistics 100(4):609–618.

City of Sumner v. Walsh, 148 Wn. 2d 490 (WA 2003). https://casetext.com/case/city-of-sumner-v-walsh

Cohen, L. E., and Felson, M. 1979. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review 44(4):588–608.

Cole, D. 2003. The effect of a curfew law on juvenile crime in Washington, D.C. American Journal of Criminal Justice 27(2):217–232.

Development Services Group, Inc. 2015. “Status Offenders.” Literature review. Washington, D.C.: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://www.ojjdp.gov/mpg/litreviews/Status_Offenders.pdf

Diviaio, D. 2007. The government is establishing your child’s curfew. Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development 21(3):797–835.

(FBI) Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2019a. Crime in the United States, Arrests by Age, 2019. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice (USDOJ). https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/topic-pages/tables/table-38

(FBI) Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2019b. Crime in the United States, Offense Definitions. Washington, DC: USDOJ. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/topic-pages/offense-definitions

Graham, H. and McIvor, G. 2015. Scottish and International Review of the Uses of Electronic Monitoring. Glasgow, Scotland: Scottish Center for Crime and Justice Research.

Grossman, E.R., and Hoke, K. 2015. Guidelines for Avoiding Pitfalls When Drafting Juvenile Curfew Laws: A Legal Analysis. Louis UJ Health L. & Pol'y 8: 301.

Grossman, E.R., Jernigan, D.H., and Miller, N.A. 2016. Do juvenile curfew laws reduce underage drinking? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 77(4):589–595.

Grossman, E.R., and Miller, N.A. 2015. A systematic review of the impact of juvenile curfew laws on public health and justice outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 49(6):945–951.

[Harvard Law Review] The Harvard Law Review Association. 2005. Juvenile curfews and the major confusion over minor rights. Harvard Law Review 118(7):2400–2421.

Hazen, K.P., and Brank, E.M. 2018. Juvenile curfews. The Encyclopedia of Juvenile Delinquency and Justice, edited by C.J. Schreck. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley–Blackwell, 470–474.

Hemmens, C., and Bennett, K. 1999. Juvenile curfews and the courts: Judicial response to a not-so-new crime control strategy. Crime and Delinquency 45(1):99–121.

Herman, D.A. 2007. Juvenile curfews and the breakdown of the tiered approach to equal protection. New York University Law Review 82:1857–1894.

Hernández, A. 2023. Cities are embracing teen curfews, though they might not curb crime. Maryland Matters (August 28). https://marylandmatters.org/2023/08/28/cities-are-embracing-teen-curfews-though-they-might-not-curb-crime/

Hockenberry, S., and Puzzanchera, C. 2023. Juvenile Court Statistics 2020. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice. https://www.ncjj.org/pdf/jcsreports/jcs2020.pdf

Hockenberry, S., and Puzzanchera, C. 2024. Juvenile Court Statistics 2021. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice. https://www.ncjj.org/pdf/jcsreports/jcs2021_508Final.pdf

Kaminsky, T. 2003. Rethinking judicial attitudes toward freedom of association challenges to teen curfews: The First Amendment exception explored. New York University Law Review 78(6):2278–2304.

Korecky, A. 2016. Curfew must not ring tonight: Judicial confusion and misperception of juvenile curfew laws. Capital University Law Review 44(4):831–872.

Kline, P. 2012. The impact of juvenile curfew laws on arrests of youth and adults. American Law and Economics Review 14(1):44–67.

LeBoeuf, D. 1996. Curfew, an Answer to Juvenile Delinquency and Victimization? USDOJ, Office of Justice Programs (OJP), Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/curfew.pdf

Leiber, M.J., Richetelli, D.M., and Feyerherm, W. 2009. Assessment. In Disproportionate Minority Contact Technical Assistance Manual, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP.

Norton, D.E. 2013. Why criminalize children? Looking beyond the express policies driving juvenile curfew legislation. In Child Versus State: Children and the Law, edited by J.W. Steverson. England: Routledge, 247–275.

Middleman, A. 2015. Comment: In the street tonight: An equal protection analysis of Baltimore City’s juvenile curfew. University of Baltimore Law Forum 46(1):Article 3. http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/lf/vol46/iss1/3

National Youth Rights Association. 2024. Curfew Laws by State. Hyattsville, MD. https://www.youthrights.org/issues/curfew/curfew-laws/#info

Office of the Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice. 2023. Juvenile curfew enforcement pilot program.Washington, DC. https://dmpsj.dc.gov/page/juvenile-curfew-enforcement-pilot-program

(OJJDP) Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. n.d. Juvenile Justice Reform Initiative in the States 1994–96. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/reform2/ch2_c.html#:~:text=Yet%20other%20critics%20argue%20that,of%20a%20group%20of%20individuals

(OJJDP) Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 1996. Curfew: An Answer to Juvenile Delinquency and Victimization? Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/curfew.pdf

Pita Loor, K.J. 2019. When protest is the disaster: Constitutional implications of state and local emergency power. Seattle University Law Review 43:1–70.

Pollack, D., and Russell, K.N. 2021. Are juvenile curfew laws effective crime stoppers? New York Law Journal 1–4. https://www.law.com/newyorklawjournal/2021/04/16/are-juvenile-curfew-laws-effective-crime-stoppers/

Pupo, J.A., and Zane, S.N. 2021. Assessing variations in juvenile court processing in urban versus rural courts: Revisiting “justice by geography.” Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 19(3):330–354.

Puzzanchera, C., Hockenberry, S., and Sickmund, M. 2022. Youth and the Juvenile Justice System: 2022 National Report. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/publications/2022-national-report.pdf

Quinn, M.C., Copeland, T., Hopkins, T., and Brody, M. 2022. A more grown-up response to ordinary adolescent behaviors: Repealing PINS laws to protect and empower D.C. youth. University of the District of Columbia Law Review 25(1):1–27.

Qutb v. Strauss, 11 F.3d 488 (5th Cir. 1993). https://casetext.com/case/qutb-v-strauss

Ramos v. Town of Vernon, 353 F.3d 171, 331 F.3d 315 (2d Cir. 2003). https://casetext.com/case/ramos-v-town-of-vernon-3?resultsNav=false

Ruefle, W., and Reynolds, K.M. 1995. Curfews and Delinquency in Major American Cities. Crime & Delinquency 41(3):347–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128795041003005

(SBB) Statistical Briefing Book. 2022. Youth Arrest Rate Trends. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/crime/JAR.asp

(SBB) Statistical Briefing Book. 2023a. Case Rate Trends: Curfew Offenses (Cases per 1,000 youth ages 10–upper age by race). Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/statistical-briefing-book/court/faqs/jcscr_display?ID=qa06283

(SBB) Statistical Briefing Book. 2023b. Case Rate Trends: Curfew Offenses (Cases per 1,000 youth ages 10–upper age). Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/court/JCSCR_Display.asp?ID=qa06263

(SBB) Statistical Briefing Book. 2023c. Characteristics of Petitioned Status Offense Cases Handled by Juvenile Courts, 2021. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/statistical-briefing-book/court/faqs/qa06603#:~:text=Q%3A%20What%20are%20the%20characteristics,white%20youth%20accounted%20for%2060%25

(SBB) Statistical Briefing Book. 2023d. Probation as a Court Disposition. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/probation/qa07101.asp?qaDate=2020

(SBB) Statistical Briefing Book. 2023e. Percentage of Petitioned Status Offense Cases Detained, 2005–2021. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP. https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/court/qa06703.asp?qaDate=2021

Stoddard, C., Steiner, B., Rohrbach, J., Hemmens, C., and Bennett, K. 2015. All the way home: Assessing the constitutionality of juvenile curfew laws. American Journal of Criminal Law 42(3):177–211.

Sutphen, R.D., and Ford, J. 2001. The effectiveness and enforcement of a teen curfew law. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 28:55–78.

Taylor, A., Guevara, L., Boyd, L.M., and Brown, R.A. 2012. Race, geography, and juvenile justice: An exploration of the liberation hypothesis. Race and Justice 2(2):114–137.

Ugwu, N. 2022. Chicago is not a sundown town: A closer look at youth curfews. Public Interest Law Reporter 28(1):1–14.

Urban, L.S. 2005. Deterrent Effect of Curfew Enforcement: Operation Nightwatch in St. Louis. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, National Institute of Justice.

Wallace, L.N. 2020. Baltimore’s juvenile curfew: Evaluating effectiveness. Criminal Justice Review 45(2):171–184.

Wilson, D.B., Gill, C., Olaghere, A., and McClure, D. 2016. Juvenile curfew effects on criminal behavior and victimization: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 12(3):1–97.

Yeide, M.K. 2009. Model Programs Guide. Curfew violation. Literature Review. Washington, DC: USDOJ, OJP, OJJDP.

Suggested Reference: Development Services Group, Inc. 2024. “Youth Curfews.” Model Programs Guide. Literature Review. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/youth-curfews

Prepared by Development Services Group, Inc., under Contract no. 47QRAA20D002V.

Last Updated: October 2024