By Youth Court Administrator Paul Bowen and Drug/Intervention Court Coordinator Katie Mitchell

Our court focuses on young people ages 14 to 17 with substance use disorders who have committed nonviolent delinquent offenses. The goal is to intervene before substance use leads to serious criminal behavior. Our program includes court appearances, regular drug tests, meetings with a probation officer, substance abuse treatment, and the engagement of families in the recovery process. In all of our work, we strive to adhere to a framework of best practices developed by OJJDP in partnership with a research team, experts in the field, and other federal agencies.

In 2016, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) selected our court to participate in the OJJDP-funded Juvenile Drug Court Learning Collaborative. The project provides training, ongoing coaching, and evaluation to improve juvenile drug treatment court programs. A fiscal year 2018 OJJDP grant also helped us improve service delivery and programming.

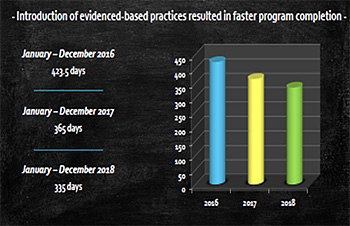

Between 2016 and 2018, the average length of time for program completion at the Rankin County Juvenile Drug Treatment Court dropped from 423.5 days to 335 days.

Between 2016 and 2018, the average length of time for program completion at the Rankin County Juvenile Drug Treatment Court dropped from 423.5 days to 335 days.We attribute this progress to a number of factors, including improved data collection, evidence-based substance abuse treatment, and family engagement.

We now collect data across a range of domains, including the number of days kids are in the program, the ratio of incentives to sanctions, the number of days in detention, graduation rates, and recidivism rates. We also break down the data by gender and race. Once we began collecting data, we realized our program was not achieving the outcomes we wanted. For example, the program was originally designed for 12 months, but the data showed that kids were in the program for much longer. This deep dive into the data offered proof for the team that change was needed along with a way to track our progress on an ongoing basis.

We have worked closely with Region 8 Mental Health Center, our outpatient treatment provider, to ensure the use of evidence-based treatment models. We were able to use grant funding to pay for the training of Region 8 counselors in evidence-based treatment models. The models we’re using now include Seeking Safety, which is specifically designed for clients with substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorders. Another model we use is the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach, which aims to increase a family’s educational, vocational, and social supports. It used to be that the court and the treatment provider operated in different lanes. But the two lanes have merged somewhat. Now there is close coordination and collaboration. We used to meet only once a year; now we meet quarterly with the Region 8 administrators to discuss staff and training needs, grant requirements, and other matters.

Engaging parents in the drug treatment court program is essential to positive outcomes. We use the Parent Project model, a series of classes designed to reduce family conflict and juvenile crime, in addition to improving school attendance and performance. The program identifies ways to address family conflict, poor school performance, teen drug use, and many other issues. The class empowers many parents to handle challenging adolescent behaviors on their own. Before they begin the class, parents may feel isolated, but after the first class they realize they are not alone in their problems. Many parents continue meeting with other members of the class on an informal basis because they find peer support helpful.

Finally, we have effective and engaged judicial leadership. Judge Thomas Broome encouraged us to jump in and embrace the NCJFCJ Learning Collaborative, and he is our biggest cheerleader. If you don’t have strong leadership and someone pushing from the top, it is difficult for change to happen. Judge Broome is hands on with the kids and knows them all by name.

We get messages from our graduates saying that their experience in juvenile drug treatment court changed their lives. They say how important it was to have someone believe in them and motivate them. Those messages are a special inspiration to all of us on the court team.

Resources:

Read an Office of Justice Programs blog on how the court team in Rankin County and other OJJDP grantees are adapting their practices during the COVID-19 epidemic to continue supporting youth on the road to recovery.

The OJJDP Model Programs Guide provides evaluations of juvenile and family drug court programs and a review of research on drug courts.

Access more information about OJJDP’s drug court programs on the Office’s website.

_______________________Points of view or opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.